Many people know that the initial design of the Space Shuttle was a matter of dispute between the NASA engineers and officials on one hand and the Nixon White House and the budget hawks within the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) on the other. The final design, after much negotiation, was a compromise between cost and performance. NASA was able to keep a large 4.5 by 18 meter cargo area, but was convinced to use a solid fuel booster strap-on to propel the shuttle into orbit. This combination of a solid booster with the liquid fueled Shuttle orbiter was intended to reduce cost but over time it proved to increase cost while adding major risk elements. The exploding foam insulation that separated the Shuttle orbiter from the Solid Rocket Booster was officially ruled the cause of the Columbia failure. The Columbia failure led to a nearly three year suspension of Shuttle launches and added nearly $3 billion in costs to the Shuttle program and perhaps billions more to the International Space Station due to the years of delay while the Shuttle was grounded.

Solid boosters have been effectively used for heavy lift cargo but they are questionable launch systems when human crews are aboard. Once ignited, solid boosters cannot be shut down, a condition that precludes effective astronaut escape capability. In many ways the “flawed design” of the Shuttle can be traced back to the initial decisions with regard to Space Shuttle design in the 1969 to 1972 time period.

After Apollo: What Next?

President Nixon speaks with the Apollo 11 crew, in quarantine after their historic mission (Credits: NASA).

In the United States, 1972 was a presidential election year and the big space question at the time was “What comes after Apollo?” President Nixon wanted to sustain an American lead in the space race against the Soviet Union, but did not want to spend big bucks to do so. The answer that had begun to evolve as early as 1969 was the Space Transportation System (STS) – now popularly known as the Space Shuttle. But there were key technical and management issues very much up in the air. What exactly would a Space Shuttle entail in terms of technical design? And how much would it cost?

A historical review of the Nixon administration’s Shuttle decision four decades ago indicates that space safety was virtually absent from the critical decision-making discussions. Efforts to cut costs dominated the discussion, ultimately adversely affecting the design integrity of the Shuttle, reducing its safety. The OMB recommended cutting NASA’s budget sharply. The cuts for fiscal year (FY) 1973 would have been $205 million, followed by a $400 million for FY 1974 year and a $1.1 billion for FY 1975. Proposed options that would have achieved these cuts were the downsizing of the Shuttle, cancelling Apollo 16, 17, and 18, closing some NASA Centers, and reducing international programs with the Soviet Union.

Few people know just how bruising and difficult that decision process actually was. The White House objective was clearly to keep NASA expenditures in the post-Apollo age under control. OMB had both NASA programs and Centers in their cross hairs. Documents from the recently released private archive of Nixon White House official Clay T. (Tom) Whitehead reveal that the Space Shuttle program – like the 2006 Hollywood comedy of the same name – might have gone down in history as the “Failure to Launch” program.

Contradictory Objectives

The original concept was to use the shuttle as a staging ground for planetary exploration and to establish a space station. That scope was narrowed when the requested $24 billion budget came back as $6 billion (Credits: NASA).

The Nixon White House had two contradictory objectives in 1970 and 1971. On one hand, they wanted to get what they considered to be wildly expensive NASA spending on the Apollo Program – a legacy from Presidents Kennedy and Johnson – under control and to establish a “normal level” of space expenditure. On the other hand, the Nixon White House also wanted a new and exciting space initiative to replace the popular Apollo program, one that promised continued American space leadership.

This new space initiative from the Nixon Administration quickly became known as the Space Shuttle. It was conceived of as a “space truck” that would, at least in concept, offer low cost and reliable access to low Earth orbit. Advocates proceeded to promote this new initiative to provide competitive launch costs for commercial satellites and also allow projects like a space station or manned space missions in low Earth orbit to be undertaken at reasonable cost.

The papers from the Whitehead archive reveal a significant tug of war between ways to cut NASA’s “unrealistically high spending” on the Apollo program and yet still initiate an exciting new space program. It appears that there were several officials in the Nixon White House and OMB who were designated to sort out this difficult issue.

Line responsibility fell to one of Nixon’s Presidential Assistants, Peter Flanigan. Flanigan turned to the President’s Special Assistant Tom Whitehead, formerly a Rand economist who had three graduate degrees from MIT and was charged with policy authority over all science agencies.

All of the key people worked with NASA Administrator James Fletcher and NASA scientists and engineers to seek out a compromise design for a curtailed version of the STS on which both President Nixon and White House staff and NASA officials could agree. Different sized Shuttles were considered. Versions that were all liquid fueled and self-contained and other designs with a solid fuel booster were evaluated for performance and cost. Safety was simply “assumed” in all the alternative designs. Finally, different and longer development periods were considered along with options like using the Titan III or Atlas for booster lift capability. The objective became to drive the cost of developing and building the Shuttle down by $15-$16 billion to levels that were under $9 billion.

The budgetary knives also targeted a shutdown of the Marshall Space Flight Center, since conventional rockets were thought to be less important once the Shuttle was available, and the Jet Propulsion Lab, after several planetary missions were over. Ames Research Center was slated for staff reductions and Wallops and what is now known as Glenn Research Center went on the chopping block. Ultimately none of these cuts were made, but efforts to cut NASA funding in significant ways left few programs safe from budgetary scrutiny.

Top-Down Decisions

On January 5, 1972, President Nixon announced the Shuttle Program. He is pictured here with NASA administrator James Fletcher later that day (Credits: NASA).

Initially NASA had considered a payload bay area for the Shuttle as long as 26 meters and its design was initially based entirely on liquid fueled propulsion. Liquid fueled engines – as opposed to solid-fueled rockets – can be instantly commanded to shut down and thus facilitate a crew escape capability. Relatively early in the tug of war with OMB, NASA management agreed to add an external solid-fuel tank to reduce the development costs. Part of the dynamic in these considerations involved the advocates from western states who promoted Utah-based Thiokol as the developer of the solid fuel booster. These states used professional lobbyists to actively intervene in the Shuttle discussions to promote the use of the solid rocket booster.

The decision to include the solid rocket booster was clearly taken from the top down and without consideration of the implications for crew escape capabilities or even the possible complications that might, in fact, boost rather than reduce cost.

Other budgetary cuts that were advocated by OMB in its recommendations for NASA were to undertake new space development in a modular fashion, allowing common use of these modules by NASA, the Department of Defense, and commercial entities with little or no change. This could reduce spending on manned space while allowing some increases for space applications and aeronautics.

The concern of the White House staff, specifically Flanigan, Whitehead, and Special Assistant to the President Jon Rose, was that in its eagerness to contain the NASA budget OMB was proposing economies in the design of the shuttle based upon presumed engineering expertise that it did not have.

It was Whitehead who sought to be the voice of reason and prudent compromise. “We succeeded when we first came into office in averting NASA’s high flying plans for space stations and Mars trips, and in bringing the budget down to a more realistic level consistent with the President’s wishes,” he wrote in a memo to Flanigan. “It was, however, our intention not to continue to erode NASA’s budget indefinitely, but to induce them to come up with a sound, forward-looking evolutionary space program for the coming decade that would not lock the President into excessively large budgets now or in the future.”

Whitehead’s memo – dated in December 1971 just before the Shuttle was formally announced – largely argued the NASA position for a Shuttle program that seemed reasonable and achievable:

“…OMB and NASA have been bickering, principally about the space shuttle. I held a series of meetings to bring the various Executive Office groups together and met with Jim Fletcher, I hope to some constructive effect. …Jim has done what I believe

to be an outstanding job of devising a space shuttle concept that is consistent with reasonable budget levels and sensible technology, and still builds for the future. Without burdening you with all the ins and outs of how we got from there to here, the debate is now focused around two shuttles…I tend to believe the larger shuttle is the more prudent course…I suspect OMB will try to push fairly hard for the smaller version. NASA might buy this as a last choice, but the impact on their morale and that of the aerospace industry would be unnecessarily negative.”

It would appear that Whitehead’s arguments carried the day. Just a month later, President Nixon announced the larger version of the Shuttle and two more Apollo flights. But the problem remained that instead of the Shuttle being designed from the “bottom up” based on systems and safety analysis, it was designed from the top down with unrealistic budget constraints and based on totally impossible performance expectations. This article is largely based on documents drawn from the Whitehead archive at the Library of Congress. In next issue, we conclude with the ramifications of these early decisions on the direction of the Shuttle program.

John Young (pictured here while saluting the flag on Apollo 16’s first EVA) received the news about the approval of the Shuttle program while walking on the Moon. He would later become Commander of the Space Shuttle inaugural flight (Credits: NASA).

The President Decides to Green Light the Shuttle

On January 5, 1972, President Richard M. Nixon announced in a joint press appearance with NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher the decision to design and build “an entirely new type of space transportation system” that would “transform the space frontier of the 1970s.” The system Nixon announced was rich in its expectations.

President Nixon proclaimed that “It will take the astronomical costs out of astronautics. In short, it will go a long way toward delivering the rich benefits of practical space utilization and the valuable spinoffs from space efforts into the daily lives of Americans and all people.” Nixon indicated that the Shuttle would bring a real working presence in space and perhaps reduce the cost of launch operation down to “one-tenth of those launch vehicles.” In his announcement, he indicated to that there would be two more Apollo flights, Apollo 16 and 17, but that these flights “bring us to an important decision point – a point of assessing what our space horizons are as Apollo ends, and of determining where we go from here.”

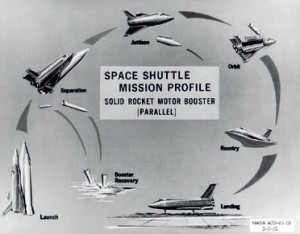

James Fletcher went on to explain that this vehicle would be able to lift some 29,000kg to low Earth orbit and could accommodate payloads that were 4.6m in diameter and 9.1m long. He indicated that the shuttle would be fueled by liquid oxygen/liquid hydrogen as well as by a solid fuel external tank that would be jettisoned before going into orbit. He promised that the Shuttle would be accomplished on a “modest budget” and that it would make space operations “less complex and less costly.”

The Shuttle Program in Historical Perspective

NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher shows the projected Space Shuttle to President Gerald R. Ford in 1976 (Credits: US National Archives).

The Shuttle program that emerged after months of discussion and compromise in 1971, the one that was actually in use for over 30 years, still provokes highly conflicting emotions. On the one hand, the Shuttle can certainly be seen as a triumph of American technology that flew over 130 successful flights to space.

Yet it can also be seen as an example of extraordinary hubris in assuming that new state-of-the-art systems can be accurately projected by costing experts and its exact technical performance prescribed before totally new technology is developed. The thought that the Shuttle could fly many dozens of times a year and bring costs down by a factor of ten turned out to be very wide of the mark. Also, the combination of a solid fuel rocket with the liquid fueled orbiter effectively limited any truly viable crew escape capability during launch operations.

The 2003 Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) stated that the Space Shuttle was “an inherently vulnerable vehicle, the safe operation of which exceeded NASA’s organizational abilities.” The CAIB report went on to state: “The increased complexity of the Shuttle, designed to be all things to all people created inherently greater risks than if more realistic technical goals had been set at the start. Designing a reusable spacecraft that is cost-effective is a daunting engineering challenge; doing so on a tightly constrained budget is even more difficult.”

The Space Shuttle prototype Enterprise flies free after being released from NASA’s 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) in the second of five free flights of the Shuttle program’s Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) (Credits: NASA).

It is easy after the fact to consider what might have been done differently. At this point in history, the Space Shuttle program is most productively seen in the context of possible lessons learned. Here are some of these possible conclusions we can draw looking back over the last forty years.

- All of the planning documents envisioned the Shuttle as a 20-year program, whose operational life would have extended from 1979 to 1998. After the Challenger accident the Rogers and Payne Commissions in 1986 indicated that the Shuttle needed to be replaced by a new vehicle in, at most, 15 years or, as simple math would indicate, it should have been replaced by 2001. Yet the Shuttle fleet flew through 2012. Thus risk assessment problems that came during the start of the program continued in the years that followed. In this regard the safety failures can be seen as that of “national space leadership” of the White House, OMB, Congress, and NASA.

- Perhaps it would have been wiser to have developed a small liquid-fueled crew-rated vehicle with an escape system for astronauts, then develop a much larger robotically controlled heavy-lift capability powered by solid fuels to allow major cost saving. This larger and more cost-efficient system could have been designed to get cargo up and down at a fraction of the cost. Space Guru Robert Zubrin has voiced this type of critique quite vividly by saying that “using the Shuttle for lifting astronauts to low Earth orbit makes as much sense as using an aircraft carrier to tow water skiers.” This splitting of crew and cargo, of course, is where current planning is going. Yet for some reason we still have solid rockets and human crew together, which from a safety perspective is not a good plan.

-

The thousands of ceramic tiles that constitute the thermal protection system for the Space Shuttle is contra-indicated in terms of operational schedule, safety, performance, and resiliency. Today’s metallic thermal systems are better in terms of performance, operational efficiency, and costs. In short, conventional rockets with capsules might have served immediate needs, allowing an additional 10 years to develop a shuttle with a much improved and cost efficient thermal control system, making it cheaper, better, and safer. Designing a human rated vehicle without developing crucial enabling technology first almost always turns out badly. The Space Shuttle was only one more case where this was true.

- The Shuttle was grounded after the Challenger and Columbia accidents for a combined total of nearly six years. A sum on the order of $3 billion was spent in making the Shuttle safe – unfortunately never with complete success. Problems with metal fatigue, the inability to access kilometers of wiring, the fragile and difficult to refurbish ceramic thermal protection system, the lack of a crew escape system – and more – suggest that the Shuttle may well have been premature and insufficiently resilient, as the CAIB report bluntly states. The Space Shuttle would never have been able to manage 39 to 59 missions a year as first envisioned. Clearly, the initial economic performance projections were dramatically off base. Realistic mission goals that avoid promising much too much to legislative bodies and a general aversion to “hype” should help our future planning for new space systems. If it seems overly ambitious in terms of technology and mission goals, then we should consider creating a different and better plan. This is where commercial systems that do not have to get budgets approved by legislative bodies clearly have an edge.

Final Observations

Today we are facing a new transition, once again with a similar drive to reduce budgets. This seems to suggest that the way forward in space transportation – at least in terms of accessing low Earth orbit – may not be by means of NASA, ESA, Roscosmos, ISRO, the Chinese National Space Agency, or JAXA, but rather through entrepreneurial innovation. In the commercial space context, risk assessment is much more likely to be central to design considerations and less likely to be part of political dynamics.

The Shuttle has played a seminal role in American space enterprise and certainly has aided the cause of international cooperation in the construction of the International Space Station. It has also provided valuable experience both positive and negative. The design of future space systems will likely involve greater use of robotics, more innovation from the private sector, and more international cooperation. One can only hope that a focus on upfront safety design will be the fourth element.

Despite its limitations, it is certain that the Space Shuttle is one of the iconic space vehicles of all time and its place in history is secure. The four decades of Space Shuttle history – from start to finish – are worthy of careful analysis to help provide clues about how to develop better and safer space vehicles to meet the demands of the future.

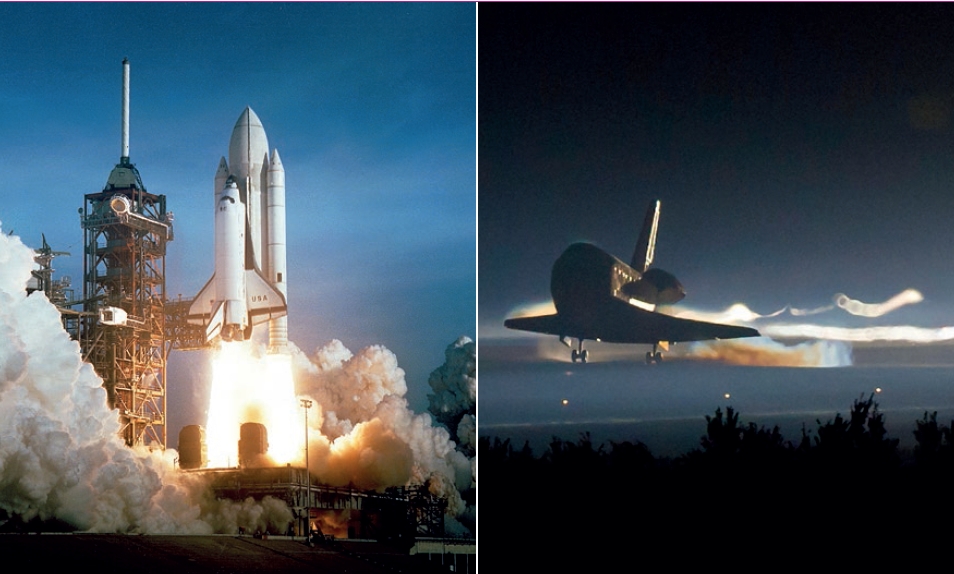

The lift off of Columbia (STS-1, 1981, on the left) and the landing of Atlantis (STS-135, 2011, on the right) mark the beginning and the end of a 31 year era of triumphs and tragedies (Credits: NASA).

This article first appeared as a two part series in Space Safety Magazine issues 8 and 9.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply