“Astronauts are stoic,” said Dr. Kim Binsted, associate professor at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa and principal investigator for the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) habitat in Muana Loa. “You ask them how they’re doing and they’ll say ‘fine.’ It’s quite difficult to get at some of the warnings that you might want to detect of conflict or a crew losing coherence. One of the ideas behind the HI-SEAS study is that forewarned is forearmed.”

The HI-SEAS project, funded by grants from the NASA Human Research Program, is a simulated Mars habitat located on an abandoned quarry near a collapsed lava tube. Inside the two-story, geodesic dome’s 146 square meter space, six-member faux astronaut crews advance personal, space-related research projects while partaking in an underlying study of team dynamics and crew cohesion.

The second and most recent crew completed its 120-day mission in summer 2014, and a new crew starts an eight-month mission October 15. The one-year mission will begin in 2015.

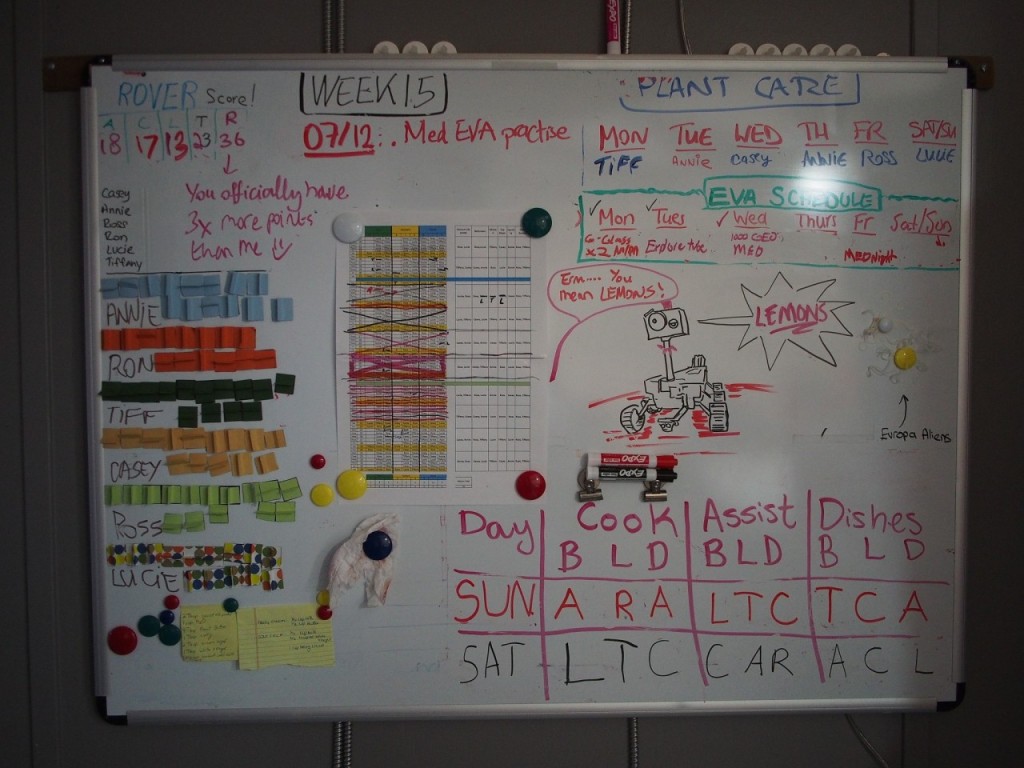

While the first HI-SEAS mission focused on astronaut sustenance, the second mission of the HI-SEAS project studied crew dynamics and cohesion inside the faux Mars habitat (left) in Hawaii, thousands of miles from family and friends (Credits: Ross Lockwood).

Monitoring the Crew

“This [second] crew has proven to be a strong team throughout the duration of the study,” said Binsted in a University of Hawaii press release. “By monitoring their interpersonal interactions, especially during times of stress, we’re learning more about the social and emotional factors that determine astronaut crew cohesion. This is a big gap for NASA right now.”

The crew filled out surveys, wrote in journals, and even wore biometric sensors to combat the ”fine” syndrome and give Binsted and her team insight into the crew’s psychological, physiological, and social wellbeing.

“We were always being studied by one method or another,” said Mission Commander Casey Stedman, an officer in the U.S. Air Force Reserve.

Crew member Ross Lockwood, a Ph.D. candidate in condensed matter physics at the University of Alberta, said the surveys became increasingly tedious as the mission continued. After all, the surveys were extensive, taking up to three hours each day. “I was pretty unhappy about being asked to fill out surveys right before bed, because that was the time of day where I was the least motivated to do mission-related work,” he explained.

Crew member Tiffany Swarmer, a researcher at the University of North Dakota’s Human Spaceflight Laboratory, echoed this sentiment. “When all you want to do is fall asleep, it is a little difficult to be motivated to fully answer and explain your answers in surveys.”

Although astronauts on a long duration mission wouldn’t necessarily be required to fill out surveys or write in journals, the crew members believe the monitoring mechanisms used in the habitat did not negatively bias the study overall and actually served the greater mission in and of itself.

“Real astronauts would have very similar schedules and feedback mechanisms for ground-controllers back home,” said Lockwood. “If anything, I’d say that those feelings [of annoyance with repetition] are exactly what real astronauts might expect, and many astronauts report feeling frustrated by the lack of flexibility in their schedules.”

Swarmer added, “Mundane repetitive tasks may have a role in future spaceflight and planetary exploration and the surveys can, to some extent, supply a source of this for analog crews. The ‘grumpiness’ or annoyance at filling out surveys could change the psych profile and survey answers occasionally, but there are enough non-bias responses to show the prevalent moods and emotional trends.”

An essential function of a team is the ability to accomplish tasks together, whether the task is making dinner or fixing a power outage in a high-stress, time-demanding environment (Credits: Ross Lockwood).

Mission Fatigue & Conflict

Repetition is a pitfall of living in space, one inherent to the so-called mission fatigue that Stedman believes serves as the greatest threat to emotional wellbeing and productivity.

“When the total of your stimuli is limited to just a few other people and enclosed inside walls, you do begin to feel the isolation and lack of variety,” he said. “Significant too, at least for me, was the inability to see the impact of our efforts. It’s important for the crew of a mission to know their actions are resulting in some positive way. With only ‘ack’—for acknowledged—as the standard reply from mission support, it can become hard to maintain the same level of excellence in one’s work if they begin to feel it ‘doesn’t matter.’”

Apathy and negativity in the highly demanding space research environment can be a costly waste of energy and time—not to mention a dangerous one—and part of the HI-SEAS study is to measure the ways crew members maintain a healthy sense of optimism and motivation. When—not if—demoralizing things do happen, how do crew members effectively cope with negative thoughts or emotions?

Swarmer’s morale was tested when she received word that one of her friends back home had sustained an injury in an accident. “My mood was affected rapidly as this was towards the end of the mission, and when I began to have obvious increased frustration I decided it was time to tell the crew as this was beginning to affect them as well,” she said.

“Tiffany was definitely exhibiting behavioral changes. She wasn’t her usual self in the morning, definitely more reserved,” recalled Lockwood. “After her disclosure, there was a noticeable change in the crew. This might have been the first time that something very serious happened that we had very little to no control over. It definitely made living in the habitat feel lonelier and more isolated.”

Above, crew members Anne Caraccio and Tiffany Swarmer use a geo tool on the barren “Martian” landscape. Fieldwork was one of the ways Binsted and her team measured the crew’s overall performance. “We gave them goals, and they accomplished them,” she said (Credits: Ross Lockwood).

Coping Mechanisms

Swarmer’s hesitation to mention her friend’s accident to the whole crew reflected the overall sentiment of the crew to address problems discreetly so as to not disrupt the mission.

“We are all motivated and self-assured achievers, and it can be hard for such people to accept help or sympathy,” Stedman said. “In order to function as a crew on Mars, we needed to operate under the assumption of near autonomy. That meant that if we could solve a crisis ourselves without consulting mission support, we did so. This was an aspect of our particular mission that was being studied. So to that end, we didn’t advertise or announce interpersonal disagreements or issues concerning the psychology we could control. That is an aspect of professionalism and culture in this environment.”

He said often, talking one-on-one with someone who could empathize on a particular issue helped lighten an emotional or mental burden. Lockwood added that the best thing a crew member could do for someone who seemed to be having a bad day was to assist in reducing workload or give that crew member extra space and time alone.

One of the main challenges came in weathering life’s daily ups and downs, not just the big stuff. Many of the crew members had to develop new coping and de-stressing mechanisms suited to the HI-SEAS environment.

“At home when I have a rough day I tend to go for a long run, take my dog on a full day hike, or even put in a funny movie. In the habitat, none of these remedies were as successful, in part due to the isolation and confinement which tended to cause fixation or hyper focus on any little issue,” said Swarmer.

“I found it beneficial to verbally tell my crew when I was having a particularly rough day or if I needed to talk. Sometimes on rough days I just wanted company during routine tasks to keep my mind off of the more stressful situations and would ask a crew member to come downstairs and sit while I prepared a meal or performed a chore.”

Outside of the habitat, Lockwood de-stresses by reading, writing, watching a show, or playing video games.

“While I was still able to make use of these strategies in the Mars habitat, they had a lower and lower payoff towards the end of the mission,” said Lockwood. “Towards the end of the mission I really invested a lot in photography and videography, which gave me time alone, but also the ability to express myself on social media. In fact, throughout the mission I derived a lot of happiness from the feedback I got from friends and family by email, and by seeing the responses I was getting through social media.”

Overall, socializing with the crew members proved to be paramount in revitalizing mood and spirit, with mealtimes the sacred space for cathartic release and community.

“We’d often offer solutions and advice during mealtimes, which became a very important time in our daily lives,” said Lockwood. “We rarely skipped mealtimes together, and our discussions were always productive and often very humorous as well.”

The crew members had to suit up to leave the habitat, a highly involved process that took hours to prepare (Credits: Tiffany Swarmer).

The Psychology of Exercise

The benefit of exercise for the body’s physical and mental state both on ground and in space is well documented. Humans are generally happier and healthier with exercise, and in space exercise carries a heightened sense of urgency. Without it, astronauts can quickly lose muscle mass and strength.

Not surprisingly, Stedman and Swarmer cited a technological fail of the habitat’s treadmill as a serious blow to motivation and morale.

“When both our treadmill and stationary bike could no longer be repaired toward the last quarter of the mission, there was a palpable distress among the crew. We all worked very hard on our personal fitness—something that is imperative during any space mission—and we used our exercise machines until they failed completely,” said Stedman. “ They were tools for a our physical and mental health. When we lost that ability to burn that energy and maintain our routine, something changed for the worse. We all compensated, but it had a telling negative effect on our morale.”

Swarmer added, “The crew suddenly had a large change in their environment leading to some decreased motivation and frustration with the loss of one of our favorite pieces of exercise equipment. To attempt to pull the crew out of this particularly odd mood, I decided some fun was in order and setup an obstacle course that the crew could complete placing a coveted prize from my provisions, a Marathon bar, to the person who could complete the course the fastest. This seemed to energize the crew—we were all laughing and seemed to shift back to normal motivation and group mood rapidly after this brief break.”

-In the video below the HI-SEAS crew describes what it is like to suit up and go out of the Mars simulation habitat:

[cleveryoutube video=”2tfu7EdzXjw” vidstyle=”1″ pic=”” afterpic=”” width=”” quality=”inherit” starttime=”” endtime=”” caption=”” showexpander=”off” alignment=”left” newser=””]

Managing Unexpected Challenges

The treadmill failure was as illuminating for Binsted and her team as it was stressful for Stedman, Swarmer, and Lockwood, and the other three crew members, Anne Caraccio, Lucie Poulet, and Ronald Williams. Not only did it clarify the equipment’s role in the mental (and not just physical) health of the crew, but it also stressed the importance of improvisation, creative capacity, and teamwork—all critical factors to understanding crew cohesion.

Binsted and her team sought to answer questions like: which crew members assume the leadership role in unexpected crisis situations? How effectively do the crew members work together to accomplish a specified goal in a specific amount of time? How well do crew members fare doing repetitive, mundane tasks in a small space?

“We were all determined to see the mission succeed, and therefore all of us put that forward of personal interests and research. Our strongest moments were when we faced adversity from factors that threatened the missions, such as systems failures. We worked best as a team when our energies were focused on the resolution of a problem we all faced equally,” said Stedman.

In addition to the broken treadmill and a simulated solar flare emergency—when the crew sought shelter in lava tubes from bursts of sun radiation—the crew also weathered other challenges.

“We experienced a number of systems failures that forced the entire crew to mobilize and use our particular talents to find solutions. I can proudly say the crew never responded with panic or indecision. We all met challenges professionally,” said Stedman. “That’s not to say there wasn’t frustration when our electric water pump failed and required repairs and an unplanned EVA [extravehicular activity] to remedy, or when our internet connection dropped and left us without any ‘in-sim’ communications with the outside for several days.”

Swarmer agreed.

“Emergency situations were dealt with very proactively. The crew tended to perform very effectively during these times with the most qualified individual taking lead and the rest of the crew taking up support positions,” she said.

Casey Stedman, above, emphasized the importance of teamwork in any highly demanding, hazardous occupation—especially spaceflight. “The benefits of having a cohesive and comfortable team prepared before a mission is to launch is absolutely more productive than just collecting x-number of highly qualified candidates into a crew,” he said (Credits: Ross Lockwood).

Creating a Team

Individual qualifications play a key role in the HI-SEAS habitat and in astronaut crew selection in general. When a team of astronauts is selected for a mission, diversity in skillsets is imperative to maintaining a safe and functional operating environment. The challenge lies in maintaining as little adversity as possible in the face of this diversity.

“The variety of scientific backgrounds, training, and education that made us experts in our fields meant we had to learn from and depend on the talents of our teammates. For a small group of highly motivated, confident achievers—type A personalities, if you will—enclosed in a small space, this naturally was a challenge,” said Stedman.

He believes finding the right crew for a long duration spaceflight comes down not to picking the best astronauts, but to picking the best team.

“Less socially aware or diplomatic individuals might never have made it through the end of the simulation,” he said. “The team that selects the crews for future space missions faces one of the greatest challenges in human spaceflight: all of these best-of-the-best, talented astronauts can perform the mission, but can they all get along with each other long enough to complete it?”

Binsted and her team—which includes researchers at seven universities across the U.S.—still have hundreds of hours worth of analysis to do on the data they collected both independently and dependently of the six crew members, and during the next two missions they will continue to observe how physical space, personality and circumstance impact crew morale and cohesion. The more the researchers discover about subtle changes in the participants’ moods, bodies, and performance, the more likely they are to prepare interventions to keep future astronauts healthy, safe, and motivated, for Mars and beyond.

Ultimately, though, the “you won’t know till you try” axiom prevails. “It takes roughly nine months to enter Martian orbit—we didn’t get the chance to see what will happen to a crew who must endure that leg of the journey. Nor the nine months it would take to return to Earth,” said Stedman. “Any crew traveling to Mars will have to be strong enough, resilient enough to maintain their focus and motivation for a much longer period than my crew had a chance to test.”

It will take an actual Mars mission to prove that the human spirit can endure and conquer this frontier, as it has others. Let’s just hope the treadmill works.

Leave a Reply