It is not an infrequent occurrence for recently retired public figures to exercise their newly found freedom to tell us all what they’ve really thought all these years. So it is with Peggy Whitson, who stepped down as Chief of NASA’s Astronaut Corps in August 2013. She was the 13th to hold that office and the first woman to do so. She is still a member of the NASA astronaut corps, but as recent comments show, she has little hope of getting back into space.

“Depending on when you fly a space mission, a female will fly only 45 to 50 percent of the missions that a male can fly,” Whitson said at an Institute of Medicine Workshop on Ethics Principles and Guidelines for Health Standards for Long Duration and Exploration Class Spaceflights, as reported by Space.com. “That’s a pretty confining limit in terms of opportunity. I know that they are scaling the risk to be the same, but the opportunities end up causing gender discrimination based on just the total number of options available for females to fly. [That’s] my perspective.”

A Russian ground crew member examines the over turned soil near the Soyuz TMA-11

spacecraft after it landed (Credits: NASA).

If anyone is an authority on pushing the boundaries for women in spaceflight, Whitson would be a good candidate. A groundbreaker throughout her career, she became the first woman to command the International Space Station (ISS), holds the record cumulative spaceflight time for a woman, and was only recently surpassed (by Sunita Williams) in number and cumulative duration of extravehicular activities (EVA) for a woman. Whitson has survived her share of old-fashioned sexism, as when Roscosmos chief Anatoly Perminov blamed the ballistic reentry and crash of Soyuz TMA-11 on the occupancy of Whitson and fellow crewmate So-Yeon Yi. “Of course in the future we will work somehow to ensure the number of women will not surpass the number of men,” Perminov said at the time. In fact, the crash came about due to a faulty pyrotechnic device.

While there was no possible justification for such comments in the case of Soyuz TMA-11, NASA’s stance on radiation hazards would seem to be justifiable. Or aren’t they?

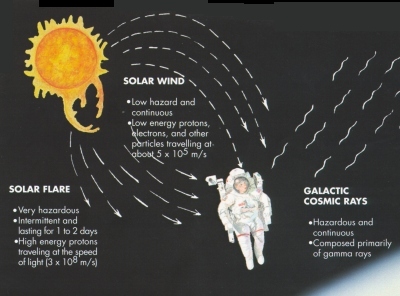

NASA’s limits on total spaceflight hours are set based on biological studies that indicate the likelihood of a human contracting cancer in response to a particular level of radiation exposure. NASA sets that limit at a 3% likelihood of contracting fatal cancer. Scientific studies have shown that women are more likely to contract cancer at a lower radiation limit than men. Therefore, a 35 year old female astronaut flying at solar minimum (when radiation is highest) would be theoretically permitted just under 5 ½ years aboard the ISS while NASA’s male astronauts could extend their spaceflights to just short of 8 years. Radiation workers, including astronauts, are supposed to be exposed to the lowest possible radiation, so those limits are almost never approached. For the record, the longest time any individual has spent in space is 2.2 years.

The question of how much risk is acceptable has always been a factor in spaceflight and spacecraft design, and NASA has at times been criticized for insufficient focus on safety, while at other times criticized for being too risk-averse. Whitson’s comments raise another question though: whose decision should it be to accept spaceflight risk?

One recent focal point for that question is the emerging commercial spaceflight market. In the United States, the plan is to permit anyone who signs an “informed consent” agreement to fly on a commercial suborbital flight. That includes the elderly, people with heart conditions, and any number of other ailments that would have precluded space enthusiasts from participating in a NASA program. There has been some controversy around this informed consent regime because, the argument is made, how is it possible for the layman to truly understand the extent of the risk to which they are consenting? How informed is that consent, really?

This concern, however, is completely irrelevant in the case of fully trained astronauts. If ever someone was qualified to make an informed decision regarding their personal flight risk, a NASA astronaut would be that one. In fact, many astronauts have been accustomed to accepting risk from their heritage as military test pilots – a risky occupation if ever there was one. But once a NASA astronaut, these professionals are carefully protected from jeopardizing their own future health.

Radiation exposure is the current Achilles heel of spaceflight. It is the primary impediment (other than money, that is) preventing human visits to Mars or long stay deep space visits. There is plenty of research into ways to mitigate radiation, but not yet any truly viable solutions. Such being the case, perhaps it’s time to allow our explorers to explore…and take the risk.

In one scenario, NASA might present astronauts with a risk assessment after each mission. The astronauts could then decide on an individual basis whether to throw their hats in the ring for another flight and if so, of what duration. This could be a completely ethical, open decision making process that both levels the playing field and keeps NASA’s nose clean.

There are many inequalities between the sexes. While some of these are physical, many more are cultural. NASA prides itself on promoting science and engineering fields to women, even in aerospace fields in which women are vastly outnumbered. NASA’s latest astronaut class is, for the first time, evenly split along gender lines: four men and four women. Permitting some freedom of decision in risk taking is one more way to ensure equal opportunity and access to space.

Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Space Safety Magazine, IAASS, or ISSF.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply