Source Space.com:

“SPACE.com caught up with Ray Williamson, executive director of the Secure World Foundation, an organization dedicated to the peaceful use of outer space, to talk about space debris, UARS, and why NASA can’t just destroy the darn satellite before it falls to Earth.”

On the reasons for the popularity of the news:

Ray Williamson: I think because we’re not used to these big satellites coming down. There are not that many, and whenever it occurs, it’s always a good idea for NASA to let people know that it’s happening. In this particular case, for example, there’s not a whole lot to worry about, but it is worthwhile being aware that it’s happening.

About the difficulty of predicting where the pieces are likely to land:

Williamson:There are a couple of things going on. One is the fact that the satellite itself is not a uniform structure; it’s composed of different pieces that have been put together. It’s partly a matter of not knowing enough. The shape of the structure is not perfectly spherical, so when it heats up and starts to break up, it will break into odd pieces. Once it begins to break up, then they can get a better sense of where this is roughly going to hit. [Related: Where On Earth Will NASA’s Doomed Satellite Fall?]

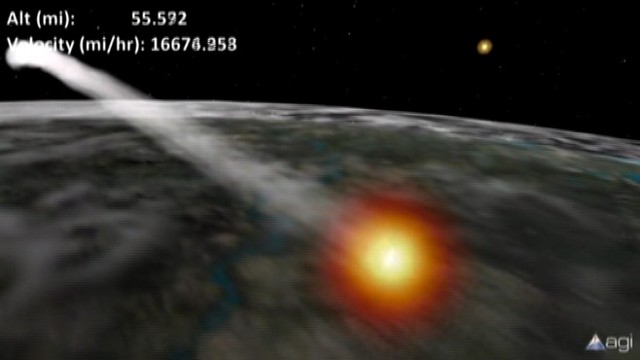

What you’d see if you could see all this happening close-up, is the pieces slowly coming apart and a trail of light, because it’s heating to the point where the aluminum structure melts. Also, it’s coming into an atmosphere that is not uniform, so since we don’t know precisely the structure of the atmosphere and what it’s hitting, there will probably be uneven heating on the satellite.

Think about the pictures that you see — the artist’s conception — of the Apollo capsule landing. If you remember seeing some of those, it was designed in such a way as to come into the atmosphere bottom first. There were ways to keep it on target as it came back, but you see this very uneven heating over the bottom of it.

About public awareness of space debris issues:

Williamson: It’s a serious issue. I directed this project that did the first space debris study for the U.S. Congress. At that point, hardly anybody knew about space debris, and I thought it was very frustrating because I could see the way things were going. It turns out a decade or two later, the issue has become so concerning to people that they have begun to pay real attention to it. I think this re-entry will certainly cause a lot of interest in people.

About cascading production of further debris:

Williamson: It’s true that there are mitigation efforts, so if you only had additional debris from launches added to what is out there, you would see that it is leveling off. But then the problem comes with what is called fragmentations, because you’ve got different debris or different satellites, say, that might have a battery short after it’s been up there for a long period of time, heats up, and explodes. Or, you could have an upper stage that was left in orbit after you launch a high-altitude communications satellite into orbit. In the past, companies left that upper stage up there and didn’t worry about whether or not the fuel was gone from it. Now, what they do is vent the fuel from the system so that it can’t eventually corrode and release fuel to cause an explosion.

About possible solutions:

Williamson:The one bright spot in that realm is that Intelsat, a few months ago, announced that it would enter into an arrangement with MDA of Canada to create an orbital servicing spacecraft that would go up to orbit and add fuel to satellites that are beginning to run out of fuel or do minor repairs, and that sort of thing. They seem to think that would be cost-effective over the long run, and if you did that, then you could find a very effective means, perhaps, for actually taking debris out of orbit. [Video: How the Refueling Satellite Will Work]

If you can add fuel to it and so forth, you can also perhaps clamp on a propulsion package to a dead satellite and send it to a higher orbit, which would effectively get it out of the way, and it would stay up there for many thousands of years. There are some technology people beginning to become really interested, but the cost issue is the real bear.

But, the other thing that one worries about at that point is if you create one heck of an anti-satellite device. It’s dual use, so that’s the third issue for me. Any time you can have a removal from orbit, you also run the risk of making an anti-satellite weapon, and then you have a hard time convincing people that it’s legitimate.

Read the full article on Space.com.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply