October 4 is the US release of the space thriller motion picture “Gravity.” Directed by Alfonso Cuarón and written by Cuarón and his son Jonás Cuarón, “Gravity” tells the story of a couple of astronauts, Ryan Stone and Matt Kowalski, are stranded on a spacewalk during a repair mission to the Hubble Space Telescope when their Space Shuttle is destroyed by debris from an unfortunate anti-satellite test. Although its worldwide release is just kicking off, “Gravity” has been featured at numerous film festivals over the past few months to universal acclaim. But “Gravity” isn’t just good cinema: a good bit of this film bears a striking resemblance to real life.

“Gravity” astronauts Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) repair the Hubble Space Telescope (Credits: Warner Bros.).

“Scary, almost, how accurate it was,” says NASA astronaut Dr. Mike Massimino. If anyone is in a position to judge, Massimino would be that one: a skilled mechanical engineer with specialties in robotics and extravehicular activities (EVA), he was the real life astronaut tasked with fixing Hubble on the Space Shuttle’s final repair mission to the space telescope in 2009. During 16 hours of EVA, Massimino struggled through stuck handrails and frozen bolts to get the telescope back in order. Four and a half years later, he got a blast from the past when he was invited to an early viewing of “Gravity.” “Nothing was out of place, nothing was missing,” Massimino told Space Safety Magazine rather wonderingly. “There was a one of a kind wirecutter we used on one of my spacewalks and sure enough they had that wirecutter in the movie. And the Hubble looked like the actual Hubble. So they did a lot of work in making sure they got all the accuracy of that stuff correct.”

Astronauts Mike Massimino (right) and Michael Good repair the Hubble during STS-125 (Credits: NASA).

That’s not to say “Gravity” is too strict about the limitations of the laws of physics, which Massimino intimated might be a good thing. “I think they took some liberties because if you looked at the way a real spacewalk goes you wouldn’t have much of a movie. It’d be kind of boring.” Of course, the element of the movie that makes sure its audiences are never bored is the constant danger Sandra Bullock’s Stone and George Clooney’s Kowalski face. While certainly dramatized for effect, the hazards of space portrayed in “Gravity” are another element that hews close to home. “It shows that space is a dangerous business,” says Massimino. “You always worry about having a bad day and they had a really bad day in the movie. But I think it does show that things can happen and those are the type of things that we worry about happening to us when we get ready to fly into space.”

“Gravity” astornaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) reaches to secure his tether during EVA (Credits: Warner Bros.).

Take space debris, for instance. Orbital debris is a constant hazard to craft and crews, as evidenced from the bullet-like holes that appear in the International Space Station from time to time. That danger is actually exacerbated at the Hubble’s altitude. “Hubble’s 100 miles higher than the space station, so the debris field is much greater up there.” In fact, on Massimino’s STS-125 mission, the crew was careful to drop to a lower altitude as soon as their Hubble repairs were finished, even though they had several days left in space.

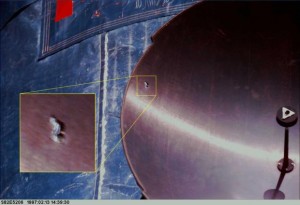

The hole in Hubble’s antenna where an orbital object stuck. “It was going pretty quick when it hit,” says astronaut Mike Massimino (Credits: NASA).

“On the real Hubble the [high gain] antenna has a hole in it the size of a silver dollar where a rock or a something came flying through its path and put a hole right through the antenna dish,” Massimino recounts. “And when we took out the wide field camera from the Hubble we saw it back on the ground at the Jet Propulsion Lab, [the exposed radiator] acted like a kid had got it with a BB gun.”

Massimino and his crewmates were trained in how to respond to debris strikes while on orbit – whether that meant repairing their ship so they could reenter the atmosphere safely, or getting their EVA partner to safety after a depressurizing puncture in a spacesuit. But they were never presented with a scenario like the one in “Gravity.” “You don’t practice dying in the simulator,” Massimino noted.

![Figure 1. Monthly Number of Objects in Earth Orbit by Object Type [5]](https://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/space-debris-accumulation1-300x205.png)

The population of orbital debris spiked in 2007 following an ASAT test (Credits: Orbital Debris Quarterly).

A field of debris the size of that shown in “Gravity” taking out a Space Shuttle is pretty unusual…but not unheard of. An event much like the anti-satellite (ASAT) test shown in the movie actually took place in 2007 when China demonstrated its capabilities in that arena by shooting one of its defunct weather satellites, the Fengyun 1C. The United States responded by shooting down one of its old satellites, USA193. By the time they were done, there were over 3000 new debris objects, showing up as a sharp spike in debris population graphs. Although USA193 fell back to Earth, it is still necessary to dodge bits of Fengyun 1C on orbit today. Preventing such ASAT tests is one of the key drivers behind international efforts to establish a space code of conduct in which nations pledge to avoid ASATs or anything else capable of wreaking such havoc on orbit.

“We have to play nice, we’re all sharing space together,” says Massimino. “You can’t just pollute the area around the Earth without consequences.”

You can see some of those consequences starting this weekend, in a theater near you.

We’ll share more insights from Dr. Massimino in our 9th issue of Space Safety Magazine, so stay tuned. Have you missed the “Gravity” hubbub? Check out the trailer below:

Image caption: The movie “Gravity” tells the story of two astronauts stranded in space after their Space Shuttle is destroyed by a debris impact during their EVA (Credits: Warner Bros.).

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](https://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Actually, such debris fields are unheard of and almost impossible. The debris field 100 km higher that ISS is more dense than at ISS altitude. Like one in a billion cubic per km compared to one in ten billion cubic km. why, because atmospheric drag burns things in. It would burn the ISS in if we did not keep boosting it back up. It was that low so that the shuttle could reach it. When the shuttle went away, the ISS was raised permanently so that we would not have to burn as often to keep it up. The article is slightly incorrect.