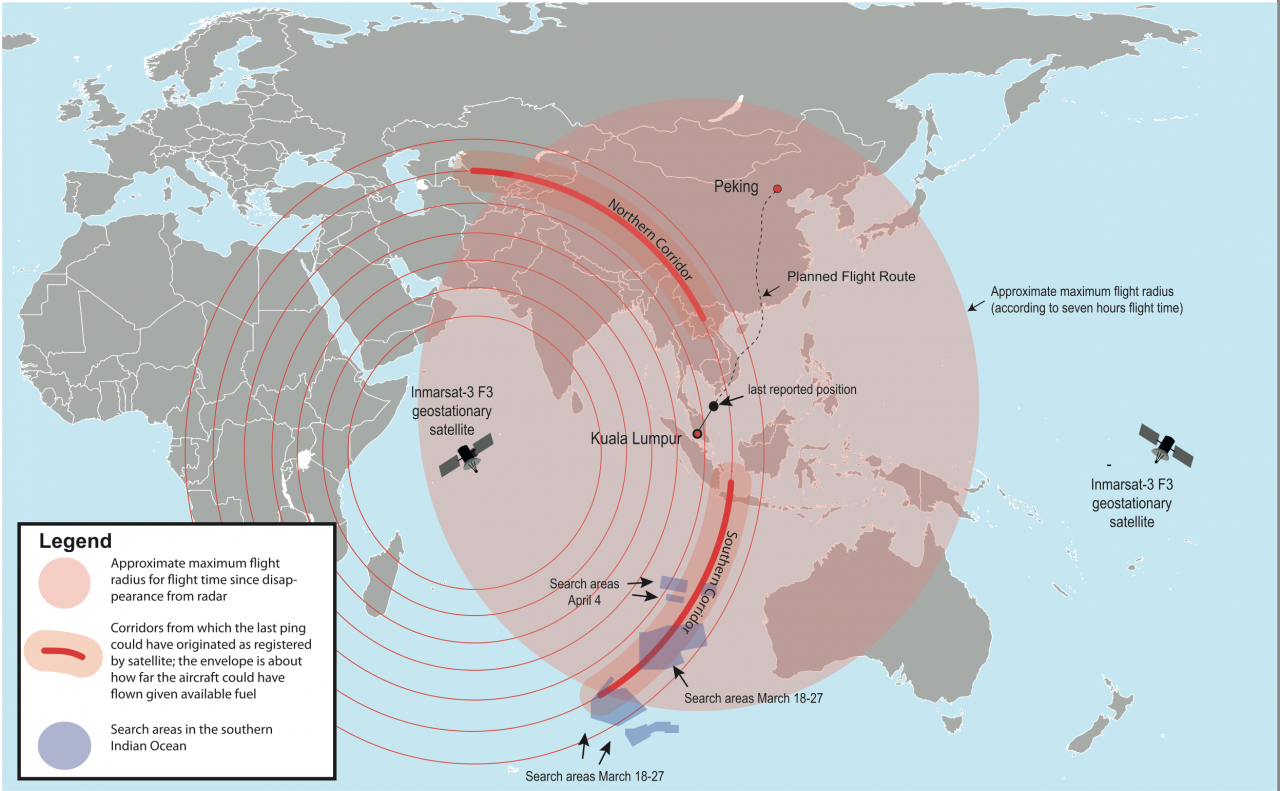

All eyes were on British satellite operator Inmarsat when it announced results of a never-done-before analysis at the end of March 2014. Looking at regular pings between Inmarsat’s network and the still airborne MH370 – a sort of confirmation of being aware of each other’s existence – the company’s analysts managed to determine the approximate location of the last received ping. Despite the fact that the exchange didn’t contain any location data, Inmarsat considerably reduced the size of the enormous haystack in which search teams from more than 20 countries were looking for the symbolic needle – the remnants of a Boeing 777-200ER.

“We looked at the Doppler effect, which is the change in frequency due to the movement of a satellite in its orbit. What that then gave us was a predicted path for the northerly route and a predicted path for the southerly route,” Chris McLaughlin, senior vice president of external affairs at Inmarsat, told Guardian in March. “That’s never been done before; our engineers came up with it as a unique contribution. Subsequently, we worked out where the last ping was, and we knew that the plane must have run out of fuel before the next automated ping,” he said.

The doomed MH370 was carrying Inmarsat’s equipment supporting the company’s Classic Aero service. A standard in aviation, Classic Aero enables transmission of data from the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) via Inmarsat’s geostationary satellite constellation.

The data usually include information about the plane’s on-board systems, its altitude, heading, speed, and location. In case of the ill-fated MH370 someone or something disabled ACARS about an hour after take-off. The regular data transmission ceased; however, the system itself kept syn- chronizing with the satellites on a regular basis as long as the computer remained powered.

In an interview with Guardian, Chris McLaughlin likened Classic Aero to a smartphone and ACARS to an app – even with the app disabled, the phone keeps performing some regular functions.

MH370 search area. — Credits: Furfur and Pechristener/Wikipedia

Free Satellite Tracking for Everyone

Since MH370’s disappearance, Inmarsat has kept a high profile. In early May, ahead of a meeting organized by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) to discuss global aircraft tracking, Inmarsat announced it will offer a basic free tracking service via its satellite fleet to all aircraft around the world already carrying its equipment.

“There is no need to wait for another technology,” Inmarsat’s Chief Operations Officer Ruy Pinto told E&T Magazine in May. “We can provide solutions that are available today. Most of the technology has been available since the Air France tragedy in 2009 and what we are trying to do now is to remove what some may consider a commercial barrier to speed up the uptake of satellite-based positioning services in the aviation community.”

Some 11,000 transoceanic airplanes around the world, nearly 90 percent of the global long-haul fleet, already carry Inmarsat’s gear – either Classic Aero or its more powerful and modern sibling Swift Broadband. While Swift Broadband offers aircraft positioning services by default, Classic Aero would require a software upgrade. Inmarsat offers to pay for that upgrade and says there is no additional investment required on the part of the airlines.

Swift Broadband, awaiting certification next year, is usually carried on top of Classic Aero. Aircraft traveling on busy transatlantic routes between Europe and North America are mandated to use satellite tracking systems, such as those provided by Swift Broadband. In the rest of the world, however, the decision is mostly upon the airlines and their willingness to invest.

Inmarsat is now working with ICAO, a UN body responsible for developing aviation standards and regulations, and the International Air Transport Association representing industry members to determine how frequently the free positioning data should be transmitted to ensure ground controllers have sufficient con- trol over the aircraft’s whereabouts.

“We think that every 15 minutes would be a reasonable interval for a free tracking service,” says Pinto. “The bandwidth available on both Classic Aero and Swift Broadband would be more than enough to accommodate such a service. Where there may be a need for some upgrade is Inmarsat and its distributors who would have to upgrade some of their ground systems to be able to provide the data seamlessly to the airlines.”

Unlike conventional radar-based tracking, Inmarsat’s satellites offer not only global coverage but also system redundancy – the company has enough satellites in orbit to cover for any unexpected failures without customers noticing.

The unmanned Bluefin 21 submarine scoured the area pinpointed as the likeliest resting place of Flight MH370 but found no trace of the aircraft. — Credits: US Navy

Streaming Black Box Data

Inmarsat, confident in its capabilities, has gone even further and proposed using its existing systems to address another painful problem that has come to light in the wake of the MH370 loss.

To understand the causes of most aviation disasters, investigators need to get hold of flight data recorders and cockpit voice recorders, better known as black boxes. Those two shoebox-sized devices usually hold all keys to explaining the most mind-boggling disasters. Unfortunately, as the case of French AF447 in 2009 as well as the recent MH370 have shown, those vital keys could lie buried at the bottom of the ocean at depths of several kilometers.

With AF447, it took search and rescue teams two years to retrieve the black boxes from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. The situation around MH370 portends that the recorders may not be discovered at all.

To help searchers in their efforts, the black boxes are equipped with locator beacons transmitting an acoustic signal on frequencies between 10 and 40 kHz. The signal propagates in water and can be intercepted at distances up to ten kilometers – that’s obviously not much if you need to scour thousands or even tens of thousands of square kilometers of the ocean and only have 30 days to do so as black box batteries are designed to last exactly that long.

In the search for AF447, the signals were not intercepted at all and sophisticated mathematical analysis had to be employed to determine the location of the aircraft’s wreckage. In the case of MH370, the search teams had a bit more luck – several signals consistent with those of the black boxes were intercepted towards the end of the 30- day period of the beacon’s battery life. In spite of that, underwater search of the area pinpointed as the most likely resting place of the aircraft rendered no positive results.

A sensible approach to prevent such a scenario from repeating in future would be to stream some black box data in real time via satellites to provide investigators with vital clues immediately after an accident. The technology enabling such streaming exists and the only thing seemingly holding it back are standards and regulations.

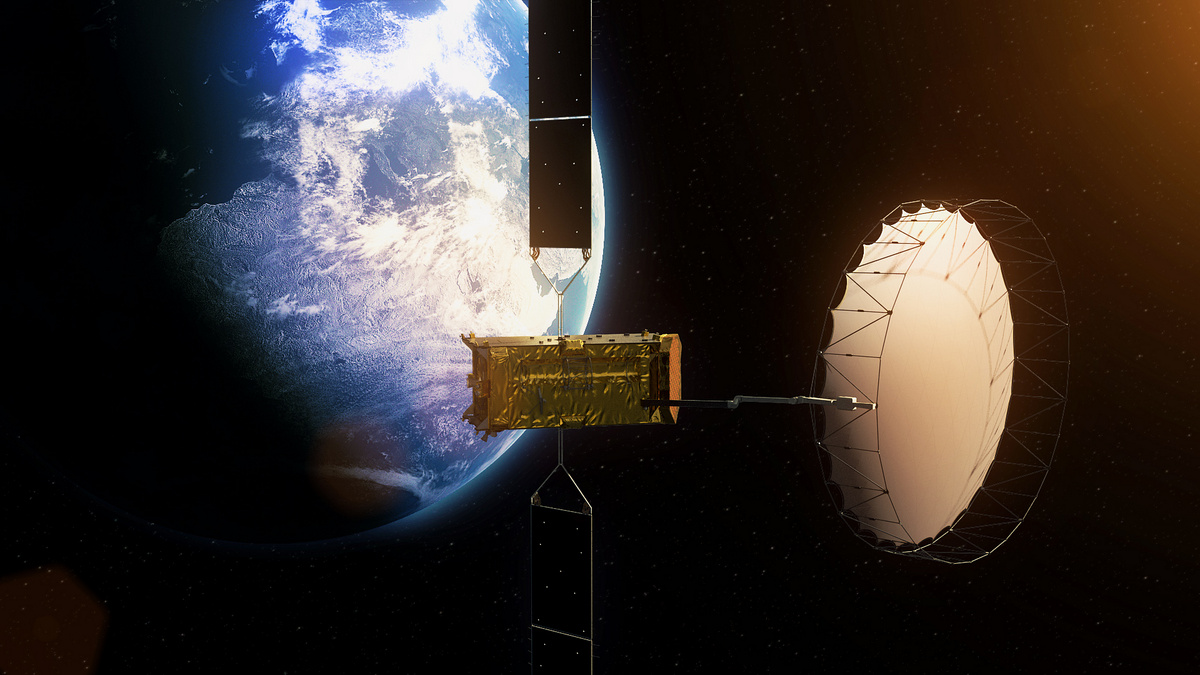

Alphasat, one of the latest additions to Inmarsat’s geostationary satellite fleet. — Credits: ESA

“We are now working with the regulatory bodies such as ICAO and IATA, as well as with the airlines, trying to define that service, the subset of data to be streamed, and how it could be implemented in Classic Aero and Swift Broadband,” Pinto told E&T Magazine. “Swift Broadband would obviously allow transmitting a bigger set of data than Classic Aero, but both are sufficient to provide a basic service, which, however, would not be a part of the free tracking offer.”

According to Inmarsat’s proposals, the data wouldn’t be streamed continuously but only after a trigger signaling unusual behaviour of the aircraft. Such a trigger could be either conveyed by the aircraft’s onboard computers or by ACARS. Apart from system failures, situations such as sudden veering off course could activate the emergency data transmission.

Data from both the flight data recorders and cockpit voice recorders would be streamed in such situations. The latter, however, poses certain privacy concerns as pilots may not be particularly keen on the prospect of their superiors possibly eavesdropping on them.

However, Inmarsat believes that potential data misuse shouldn’t be a showstopper. “We would have to invest into and adapt our systems to address the privacy concerns. Either the data could be automatically erased after a certain time or it could have a very limited access and not be available to normal operations,” Pinto told E&T Magazine. “There are ways in which you can address privacy concerns, similar to secure connections that you can see on the Internet. However, these mechanisms would have to be mandated by the regulation.”

Obviously, Inmarsat is not the only company that could possibly provide such services. Its competitors, American Iridium and United Arab Emirates Thuraya, will most likely delve into black box data streaming as well.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply