MH 370: Links Between Air and Space

On March 8, 2014, Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, also known by its IATA tag MH370, disappeared in the middle of a flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing carrying 227 passengers and 12 crewmembers. Just a few minutes after a reassuring “Good night Malaysian 370” was heard from the cockpit, someone or something disabled the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) as well as the aircraft’s radar transponder. The plane never checked in with controllers after entering Vietnamese airspace and what was supposed to be a rather uneventful flight turned into the biggest aviation mystery of all time.

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 is not the first modern-day aircraft to unexpectedly cease operations. The lack of connectivity using available and in-development satellite applications is a primary driver of the mysteries that surround aircraft disappearances. With the continuous connectivity available through space assets, controllers on the ground would be aware of challenges onboard in near real time.

These assets are not yet being utilized by most airliners. The infrastructure costs money and rely on standards. But these barriers are dwindling and a concerted international effort is underway to bring aircraft into the space age.

Precedent

Commercial aircraft accidents are not common, but when they do take place they are prone to high fatality rates. This presents a classic high impact-low probability quandary: how much should one invest to prevent an accident that is already unlikely? With the disappearance of MH370, however, the unlikely may have occurred one too many times.

The possibility of a modern commercial aircraft going missing became real in 2009, following the loss of Air France Flight 447 on June en route from Rio de Janeiro to Paris. The wreckage of Flight 447 was discovered more rapidly than MH370’s, but many of the communication issues were the same – and it was a full two years before the black box was recovered to expose the full details of the crash and its resultant loss of 216 passengers and 12 crewmembers.

In 2005, Helios Airways Flight 522 suddenly stopped responding to air traffic control. This flight, en route from Cyprus to Athens, was never out of range of ground radar and when it crashed, officials knew exactly where it was. But enhanced connectivity would have allowed ground control to determine the precise system status – a manual instead of automatic pressurization setting – and correct it before it became fatal.

There are just a few short years between each of these incidents, each breaking some record for fatalities incurred in a plane crash. With the latest and most mysterious of these lost planes, the momentum for change and the technology to achieve it may finally have converged.

A Helios Airways Boeing 737-31S at Ruzyne Airport (PRG / LKPR). This aircraft crashed on Greek soil on 14 August 2005 (Credits: Alan Lebeda).

Space Assets for Aircraft

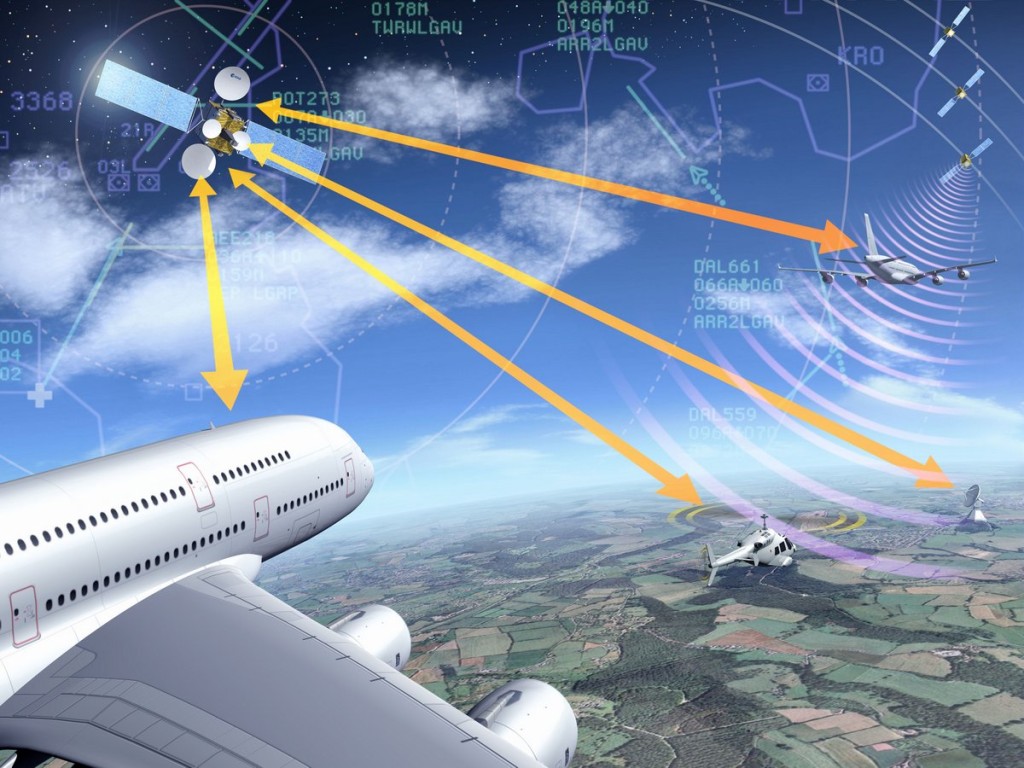

The single mechanism for improving in-flight tracking, communication, and status awareness is via satellites. Communication and navigation satellites are most critical, although Earth-observing satellites may have their place as well.

Telecom satellite connections already take place via service providers such as Inmarsat and Iridium. These services are basic and entail periodic “pings” through which the aircraft and satellite acknowledge each other’s existence, but do not identify the aircraft’s location. More communicative services are commercially available, allowing airliners to gather in-flight location and status data, for a price. These services are on the verge of expansion from niche product to mainstream. In the aftermath of MH370’s disappearance, Inmarsat announced a free service expansion to include global tracking and monitoring for any aircraft with Inmarsat hardware installed – which is 80-90% of all aircraft. Airliners will likely be reevaluating the cost/benefit analysis for purchasing additional communication services in light of these events.

Black Box Streaming

One outstanding upgrade appears to have a rocky road to implementation. Flight recorder and cockpit voice recorder streaming would enable air traffic control to understand when something goes wrong as it happens instead of hours, months, or even years later when the black box finally makes it back to authorities. Streaming opens the possibility to have air traffic control assist in troubleshooting efforts, potentially averting fatal crashes. However, pilots are opposed to streaming, feeling that it violates their privacy to enable constant eavesdropping on their workplace conversations. Proposals have been made to address this concern; it is to be hoped it can be speedily resolved and the valuable streaming services implemented.

Establishing satellite communication and data link standards will bring about a paradigm shift in air traffic connectivity. — Credits: ESA

The Future of Tracking

The airline industry is demonstrating responsiveness to consumer demands for satellite services such as in-flight broadband access. It is now time to tap into those same resources to enhance the connectivity of aircraft safety systems.

Here we take a look at the current state and up and coming developments of aircraft in-flight and post-crash tracking using radar, radio, telecommunication satellites, navigation satellites, and Earth observing satellites. We examine the international mechanisms by which such resources are activated and the routine space hazards aircraft may not be prepared to handle.

Catalyst for Change

To-date, the true events that took place aboard MH370 on March 8 remain unknown. But the investigations into the disappearance have highlighted several potential technical and human engineering concerns that are worthy of further examination. They have also shone a spotlight on some remarkable international organizations that routinely respond to disasters and work to prevent their repetition.

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 has likely left a lasting impact on the relationship between the aviation industry and satellite service operators. International standards initiatives are in play and public tolerance for unnecessary risk in aircraft communications is at an all-time low. Satellite capabilities and constraints have rarely received such scrutiny.

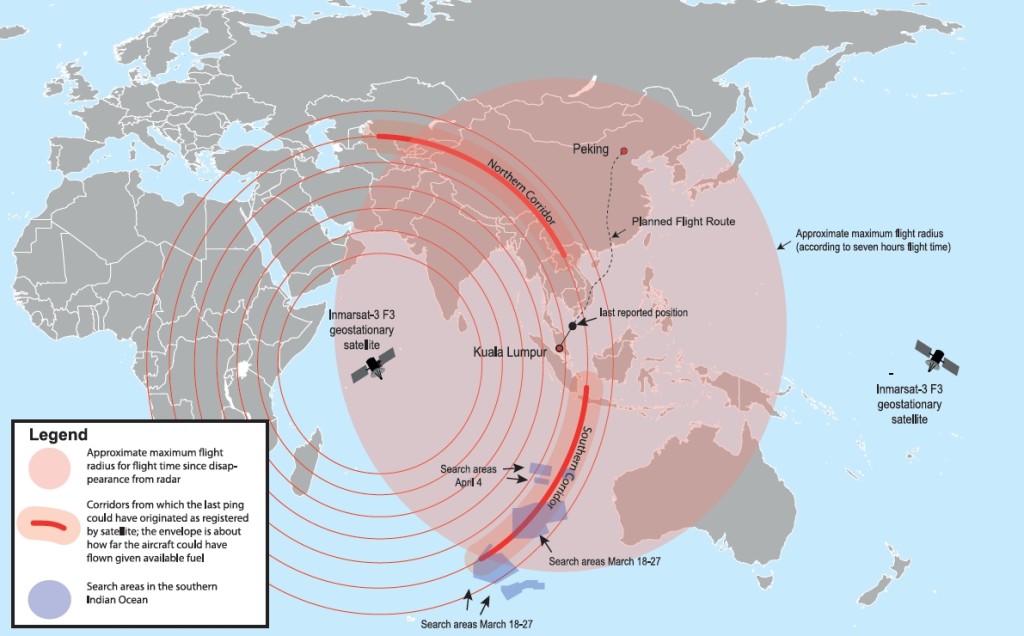

The evolution of the MH370 search area (Credits: Furfur and Pechristener/Wikipedia with translation by A. Klawitter).

Organizations

The disappearance of MH370 shone a spotlight on numerous organizations that usually operate without public notice but serve critical roles in aviation and disaster response.

ICAO

The International Civil Aviation Organization is a United Nations agency that creates standards for flight safety and cross-border aircraft operations. ICAO was created in 1944 as a result of what is known as the Chicago Convention and remains critical to the smooth operation of air traffic worldwide. It defines accident investigation procedures and contains the Air Navigation Commission (ANC) body of technical experts. The ICAO concept has been explored as the basis for a similar organization relating to spaceflight.

IATA

The International Air Transport Association is a global trade organization of airlines. It reports representing 240 airlines, constituting 84% of global air traffic. IATA works with ICAO to develop policies and conducts operational safety audits of airlines as mandated by individual national governments. It also works on security policies, fare pricing structures, and environmental impacts.

International Charter Space and Major Disasters

This international treaty engages its members in rapid responses to major terrestrial disasters by providing free access to civilian satellite imagery of affected areas. The Charter is most commonly activated for natural disasters such as floods and tsunamis. It’s activation in response to the disappearance of MH370 was a first of its kind.

Inmarsat

Inmarsat is a British telecommunication company that provides, among other offerings, satellite-based voice and data services for aircraft. Inmarsat received attention related to the MH370 when it devised a new analysis methodology to try to trace the flight path using simple automated pings. The company subsequently announced a service to provide free aircraft tracking to anyone with the appropriate equipment.

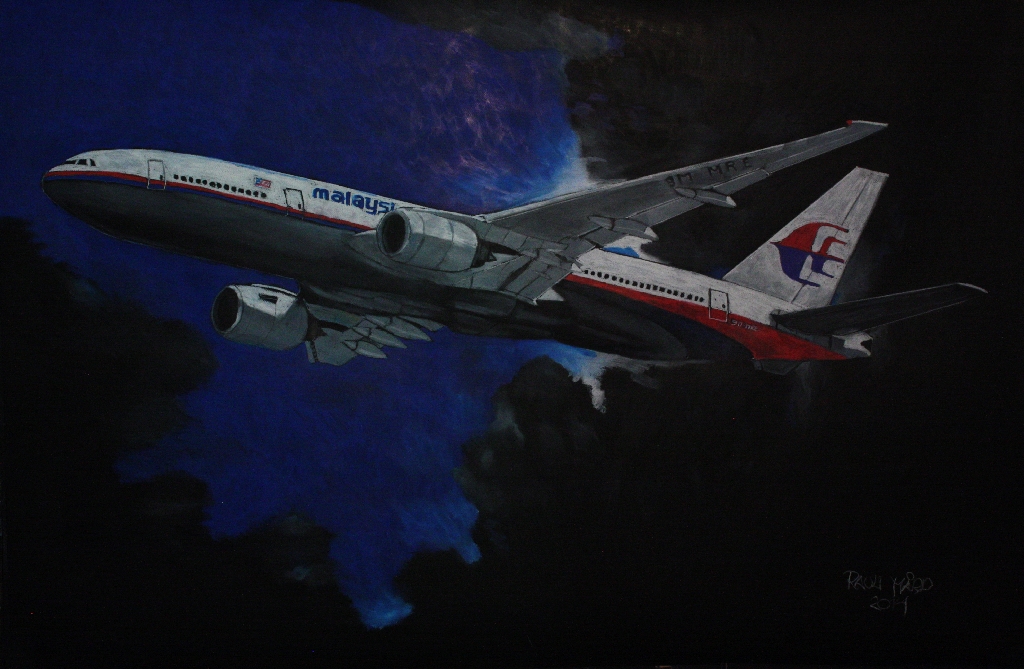

Somewhere: Art and MH370

Somewhere depicts Finnish artist Rauli Mård’s imagining of the lost Malaysian Airlines Boeing 777. Mård aptly describes himself as an analog artist in a digital time, combining his fascination with American military jetplane design – “ever since the F-4 Phantom” – and his love of the fine art heritage. Mård’s painting process begins with a precise outline followed by a detailed build up, using water-soluble crayons without water, layered in thin, partly transparent layers on black cardboard. He has always liked strong-colored skies and large canvases: “Somewhere is 40×60 inches. I couldn’t imagine any smaller size!”

Contact rauli@raulimard.com or visit www.raulimard.com to purchase the original.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)