Newly formed Planetary Resources aims to establish commercial asteroid mining (Credits: Planetary Resoures).

April 24, 2012 marked a milestone in human activities in outer space with the announcement by a group of entrepreneurs, engineers, and investors of the formation of Planetary Resources, Inc. The company, which features such investors as aerospace innovator Ross Perot, Jr. and filmmaker James Cameron, is being led by President and Chief Engineer Chris Lewicki, a former NASA Mars mission manager, and Peter Diamandis and Eric Anderson serving as co-chairmen.

The press conference outlined the company’s ambitious plan to extract resources from near-Earth asteroids. This plan is broken down into three phases. The first phase, which is scheduled to launch in twenty-four months, will deploy Earth-orbiting satellites to identify near-Earth asteroids that have potential resources for harvesting. The second phase involves sending spacecraft beyond earth orbit to provide reconnaissance of near-earth asteroids for potential exploitation of resources including water. Neither of these planned activities fall outside of the norm of the current body of international space law, and except for their commercial nature they are similar to government-sponsored missions.

However, the third phase of Planetary Resources’ plan leads into uncharted waters and potentially falls outside the current body of space law. The third phase involves deploying unmanned spacecraft to previously identified near-Earth asteroids and begins the process of extracting minerals and other resources for utilization. The question is how this plan fits within the scheme of the current body of space law and how that law will be stretched and modified to meet the challenges thrust upon it.

The Outer Space Treaty

The proposed plan by Planetary Resources to harvest resources from asteroids will implicate the Outer Space Treaty primarily in that the United States, which will likely serve as the launching State for Planetary Resources’ activities, will ultimately be responsible for the activities performed in outer space by the company. This means that the United States will not only be responsible for approving the proposed activities, but it will also be accountable for demonstrating to the rest of the international community that Planetary Resources’ activities are consistent with the principles of the Outer Space Treaty.

In their initial phase, Planetary Resources will conduct investigative operations, within currently defined law (Credits: Planetary Resources).

Extraction of extraterrestrial resources is not prohibited per se by the Outer Space Treaty; however, to the extent that extraction implicates a property interest, such an activity could be prohibited. The pertinent part of the Outer Space Treaty dealing with property rights is the prohibition on nations appropriating outer space and extraterrestrial bodies such as the Moon and asteroids as their sovereign territory. While there is no disagreement about sovereign nations claiming property rights in outer space, whether private individuals, including legal entities such as Planetary Resources, can make claims and appropriate these bodies and the resources within is up for debate.

The crux of the debate is whether an exception that allows private ownership exists within the Outer Space Treaty. This question is a matter of continuing debate with one side claiming that no such exception exists and the other claiming that it does. Until now, the debate has been abstract and both sides have proffered arguments supporting their positions. However, with the potential of actual resource extraction occurring within the decade, the stakes are substantially higher than winning an academic debate. Literally billions of dollars will be invested to perform extraction missions on near-Earth asteroids, and if the status of private property rights is not settled, the United States government may be faced with the choice of either halting Planetary Resources’ extraction activities or facing the possibly that it may be sanctioning an activity that could be illegal under international law and the resultant diplomatic and political fallout.

The Liability Convention and Indemnity

Another legal concern surrounds liability for any incidents arising out of Planetary Resources’ activities. The Liability Convention has stood as a sentinel protecting the interests of other nations for damage caused by space activities both on the surface of the Earth and in outer space. However, the effectiveness of the Liability Convention is questionable. The first time the Liability Convention was invoked during the Cosmos 954 incident in 1979, it resulted in an agreement that, while based on the duties and obligations of the former Soviet Union under both the Rescue Agreement and the Liability Convention, has been criticized since the former Soviet Union never fully compensated the Canadian government for the amount agreed to. The concern is that if Planetary Resources activities cause appreciable damage on the surface of the Earth, will the Liability Convention’s precepts be sufficient to ensure fair and just compensation?

The question of effectiveness also applies to incidents that may occur in outer space as a result of Planetary Resources’ activities. This second scenario, outlined in Article III of the Liability Convention, has yet to be tested. The incident between Cosmos 2251 and Iridium 33, which could have implicated this scenario of the Liability Convention, failed to trigger because there was insufficient evidence to determine which party was at fault and to what extent the parties were at fault. With Planetary Resources’ activities likely to increase the amount of traffic in both medium and low Earth orbit, the potential for accidents to occur will increase. The question is whether the Liability Convention as it stands today is sufficient to address the potential incidents that could be caused by this activity.

Notably, the Liability Convention implicates government responsibility for the activities of those operating under its jurisdiction and for any damages that may occur as a result. It is common practice for a launching State to require an entity performing outer space activities under its jurisdiction to provide indemnification for any damage that the government may have to pay compensation for. However, with the magnitude and scope of activities planned by Planetary Resources, the question is what is the proper amount of surety to post in the event that an accident occurs? This also begs the question that given the potential wealth that these mining operations will generate, should the amount of compensation made available to an aggrieved party go beyond what a government will offer as fair compensation?

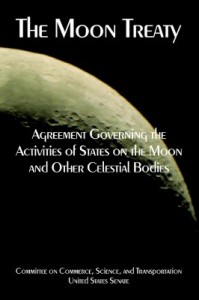

The Moon Treaty

The legal wild card in the resource extraction activities proposed by Planetary Resources is the Moon Treaty. This controversial child of the Outer Space Treaty has been rendered an outcast by the three major space-faring nations even though it has seventeen parties who have either signed, acceded to, or ratified it, which makes it binding international law. Yet, most legal scholars consider the Moon Treaty failed international law and irrelevant. However, the Moon Treaty not only deals with the Moon, but also planets and asteroids, which makes it a potential player in the planned extraction activities.

The precepts of the Moon Treaty directly prohibit private ownership, thus addressing the contentious issue left open by its parent. It also addresses resource extraction by approaching it from the point of view of wealth distribution amongst the nations of the Earth, thus subordinating profit. The Moon Treaty goes further by mandating the creation of a yet-to-be defined international legal regime to oversee the extraction and distribution of extraterrestrial resources. It is this legal regime, which is similar to one found in the original draft of the Law of the Sea Convention, that has proven to be controversial to the major space faring nations.

However, with the likelihood of resource extraction becoming a reality, the Moon Treaty may find new vigor with non-parties joining the accord and adding new voices in the chorus to make its effect as international law more pronounced. Even more so, countries such as the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China, which both refused to become part of the Moon Treaty when originally opened for signing, may decide to throw their support behind the accord instead of facing the risk of being left behind in resource extraction activities. Such support could provide sufficient political and soft-power pressure such that the United States may be forced to stall Planetary Resources’ activities until such time as it could negotiate an annex to the Moon Treaty as has been done with the Law of the Sea Convention. The effect would be to effectively stall extraction activities until the legal issues could be resolved.

Conclusion

During Planetary Resources’ press conference, the approach being planned to meet the ambitious goals set forth was likened to the revolutionary effect that the personal computer had in ushering in the information age. That analogy, while focusing on technical breakthroughs, ironically also rings through for the challenges encountered in the legal arena. Like the complex legal issues ushered in by the information age, resource extraction as envisioned by Planetary Resources will likewise usher in complex legal challenges that must be met preemptively or reactively. The question is whether the current legal regime of outer space law is ready to meet the challenges soon to be imposed upon it by the commercial activities proposed or will it crumble in favor of a new legal regime especially tailored to meet those challenges.

The video below introduces Planetary Resources:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7fYYPN0BdBw]

I enjoyed your article Michael! Especially interesting theory on other states using the Moon Treaty to prevent U.S. companies from completely capturing this new market- I can see that happening.

Back to the OST, any thoughts on its language about all use of outer space being for the benefit of all countries (even “all peoples” in the opening clauses), regardless of their economic or scientific development, creating some sort of trust (which the Moon Treaty seems to do more expressly in its mining section you mention)?

Thank you. I am glad you enjoyed the article.

Could you be more specific?

About the trust? I’m not sure if that’s the right term here, but that’s what I think of when something is held or done “for the benefit of” or “in the interest of” someone else.

In this case I’m looking at the OST’s 4th opening clause “Believing that the exploration and use of outer space should be carried on for the benefit of all peoples irrespective of the degree of their economic or scientific development”, and Article I’s “The exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development . . . . “. To me sounds like if I mine resources, I have to do it for the benefit of all peoples (or at least all nations). Which could be the vague form of what the Moon Treaty tried to detail in Article 11.7(d): “An equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from those resources . . . . “.

The OST does not create a legal trust or any other legal entity. Except for the prohibition against national appropriation of outer space and celestial bodies and the placement of nuclear weapons in outer space, the OST is essentially a set of principles that the signatories have agreed to abide by.

The treaties following the OST serve to flesh out the principles of the OST. Think of the OST as the parent treaty of the international space law and the treaties that follow (Rescue Agreement, Liability Convention, Registration Convention and the Moon Treaty) as its children.

Thanks Michael- very interesting!

And did the U.S. Senate ratify the Outer Space Treaty? If not, then any language in it is just wishful thinking by people who want the benefits of space travel without having to do the hard work themselves.

The Outer Space Treaty was ratified by the United States.

Interesting article.

Given the sheer vastness of NEar Earth Asteroids (NEAs), and asteroids/objects further afield (e.g. main asteroid belt, Kuiper Belt, Oort Cloud) this “controversy” might seem a little comically to future historians. If we ignore everything beyond NEAs, there is still a vast amount of resources that even if one country or private organization wanted to, they couldn’t possible maintain ownership of them all. I’ve even go so far as to say that you could probably give one country/entity a 25 year head start, and you’d still do okay by showing up late to the game; heck even 50 years down the road.

Separately, I really do think there will need to be a policy about returning NEAs to Earth orbit. I would think anything in LEO should be prohibited, due to the possibilty, even if remote, of said object entering the atmosphere. Small enough objects (<~5m) would generally burn up, but anything larger could become a hazard, even if accidental.

Space does seem infinitely vast, with virtually unlimited resources! Though I think back to all the times throughout history that civilizations have thought they could never possibly run out of the resources of their region/country/world. The capacity of humanity to use up whatever is available has stopped surprising me. Though I still can’t see us using up all the resources in space . . .

What might be more likely is the fight over the resources that we can actually reach at different times. Although resources throughout the universe may be unlimited, we’ll only have the capacity to reach certain areas at certain times.

i’m an indonesian and right now is taking the asteroid mining issue for my research. in this issue, i find one big problem base on the probability of damage caused by the asteroid mining. for example, if the asteroid, because of the asteroid mining, fall into the earth or crash another space object own by another country. as we know, there is only one liability convention (liability convention 1972), and the convention substance is about damage caused by space object (not celestial bodies, in this case asteroid). is it possible to use the liability convention 1972 when the damage by asteroid occurs?

Probably not. The definition of “space Objects” in the liability Convention might not include asteroids or other celestial bodies. However, Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty requires that state parties to the Treaty retain jurisdiction and responsibility for the outer space activities of its agencies and non-governmental (private) entities. Therefore, even though the Liability Convention would probably not cover damage caused by asteroid mining, national accountability would probably still vest in the nation sponsoring these types of activities.

So, there’s no way to use liability convention when asteroid (celestial bodies) causes any damage? Based on the fact that Liability Convention, as the most specific convention about liability, is not really effective when a dispute happens, I can’t imagine how worrying it is when there is only OST 1967 that we can use.

Then, is the “.. shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interest of all countries…” and “…shall be the province of all mankind” can be an obstacle to planetary resources to realize the asteroid mining?

coz i think the asteroid mining is an profit minded activity.

So, there’s no way to use liability convention when asteroid (celestial bodies) causes any damage? Based on the fact that Liability Convention, as the most specific convention about liability, is not really effective when a dispute happens, I can’t imagine how worrying it is when there is only OST 1967 that we can use.

Then, is the “.. shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interest of all countries…” and “…shall be the province of all mankind” can be an obstacle to planetary resources to realize the asteroid mining?

coz i think the asteroid mining is an profit minded activity.