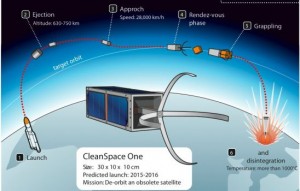

A rendition of Clean Space One shows how it will catch defunct satellites for removal from space (Credits: Swiss Space Center).

The Swiss Space Center at the Swiss Federal Institute for Technology in Lausanna, announced on February 15th its plan to develop and launch a satellite to remove space debris from low-Earth orbit. The $11-million (USD) satellite, called Clean Space One, is intended to intercept and de-orbit one of two Swiss satellites currently in orbit: the Swiss-cube picosatellite, or its cousin TIsat, which are 1,000 cubic centimeters (61 cubic inches) in size. Clean Space One is intended to rendezvous with its target, extend a grappling arm to grab it and then plunge into Earth’s atmosphere, which would result in its destruction as well as the defunct satellite during reentry. The announcement by the Swiss Federal Institute has been met with enthusiasm by the space debris community, and it holds the promise to demonstrate a viable means of space debris removal. However, in announcing this effort, the Swiss may have inadvertently provided the answer to policy questions surrounding the issue of space debris removal.

Space debris removal entails more than then technical challenges. Significant legal and policy challenges are also a substantial part of space debris removal. The legal issues surrounding space debris removal include ownership issues under international law, liability and in the case of nations such as the United States technology and licensing and export matters. However, while these issues are an impediment to space debris removal, they are not insurmountable. Political issues surrounding space debris removal are another impediment equal to or greater in scope to those presented in the legal arena. Of the political difficulties presented, the most onerous extends to the hardware and methodologies used to remove space debris from orbit because they may be construed to have potential dual use as a weapon to either disable or de–orbit functioning space objects. This political concern is embodied by the continuing efforts of the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation in their efforts to enact the draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects (PPWT). Development and use of technology and methodologies may proceed without the intent of using them for harmful purposes; however, political and diplomatic posturing by other space faring nations and non-space faring nations alike could brand space debris removal efforts as a guise for more threatening activities simply because the potential exists for the technology and methodologies to be used in a manner inconsistent with their true purpose.

The Swiss space debris removal effort, however, could side-step the space weapon debate and provide a pathway for large-scale space debris removal efforts. Switzerland has traditionally taken a neutral political stance in larger world affairs. It has no ongoing geopolitical issues with the People’s Republic of China or the Russian Federation, and it stands to reason that the planned flight of Clean Space One will not raise political objections that the use of the technology demonstrates a space weapon capability. If no objections are raised, and Clean Space One completes its mission, Switzerland may unintentionally create two routes to facilitate space debris removal en mass.

First, a successful removal by the Swiss of one of its satellites could set a customary precedent for international space law in that it would perform the otherwise unprecedented maneuver of removing orbital debris through the assistance of another space object. Performing such a maneuver without objection of the international community could establish a customary norm that a nation can de-orbit a derelict space object registered to it through the use of another space object without the interference or objection of other nations. In essence, Clean Space One could provide the legal precedent to allow space debris cleanup in the same vein that Sputnik-1 set the precedent for free passage through space.

Another path that the Swiss effort could take is to provide a neutral launching state under whose jurisdiction space debris removal efforts may be undertaken. Space debris efforts launched under the auspices of the Swiss government could allow large-scale space debris removal efforts to take place without the political objection that the means employed are a cover for the testing or deployment of space-based weapons. Such an avenue might be unsavory for the major space-faring nations; however, utilizing Switzerland’s neutrality to avoid political suspicions would also employ legal mechanisms, including consent agreements to interfere with and remove another foreign sovereigns’ derelict space objects, licensing agreements to address export controls, security clearances in the case of space objects involved in national security activities, and indemnification in the event that removal activities produce liability to the Swiss government.

Alternatively, if the Swiss government sees an economic benefit in the space debris removal industry because of its political neutrality, it might consider promulgating a domestic space law similar to the one adopted by Austria in 2011. Creating a domestic space law would help facilitate foreign non-governmental entities to create organizations under Swiss jurisdiction for the purpose of space debris removal. This would allow these organizations to perform space debris removal under Switzerland’s jurisdiction as a launching state and take advantage of Switzerland’s neutrality and the diminished scrutiny that affiliation would entail.

The Swiss announcement of its space debris removal demonstration is a positive step forward in space debris removal efforts. However, what is more encouraging is the political door the Swiss announcement may have opened. Whether the Swiss government will further open the door and invite other nations to take advantage of their political neutrality to usher in large scale space debris removal is uncertain, but the opportunity for Switzerland is apparent and ripe for the picking.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply