In the lead up to the tenth anniversary of the disintegration of Columbia and loss of all its crew on February 1, Space Safety Magazine spoke with someone who remains intimately connected with Columbia to this day. NASA’s Mike Ciannilli now serves as Project Manager of the Columbia Research and Preservation Office; on February 1, 2003, he was Columbia’s test project engineer. He spent much of the rest of that year hunting for remnants of STS-107. Looking back now, Ciannilli’s had time to absorb the events of that day and the analyses that followed. And he has some lessons for us all.

“Make sure the decisions you make are really based on facts.” Ciannilli notes that the assessment of Columbia’s initial foam strike was based on outdated tools and inaccurate models – and on that basis was not considered a safety hazard. “Know that you’re testing with the right criteria,” Ciannilli says.

“Keep vigilant when things that were once off-nominal become normal for you.” STS-107 wasn’t the first flight with foam loss. Ciannilli acknowledges that as vehicles age some things will just happen, but that doesn’t mean it’s acceptable. “You look back at the issues with o-rings for Challenger and foam for Columbia and these events were things that had a history to them,” Ciannilli says. While he notes that hindsight may be 20/20, that’s no excuse for not being vigilante of changes: “Just don’t accept them for being new and normal.”

“Listen to your vehicle. The vehicle’s talking to you, the hardware’s talking to you – listen to it.” Ciannilli describes how very small things – like the creaking of your car in the morning – may indicate bigger changes going on. “You can feel the warning signs quicker,” says Ciannilli. “Things are happening and they often start as very small things. Really listen to what you vehicle’s trying to tell you.”

“I know it’s a cliché, but communication is critical. It’s so true.” Ciannilli notes that nothing can beat an open culture for enabling free communication. There will always be some reluctant to present concerns before management with less than perfect proof; it’s management’s responsibility to reduce that reluctance as much as possible with open door policies and “walking the walk,” by rewarding those who come forward. He thinks NASA’s been able to do that in the years since Columbia, but the real test will be whether they and other organizations can keep it up for the long haul. “You gotta have it so that a technician on the floor feels confident he can elevate any concerns up the chain as far as he needs to.”

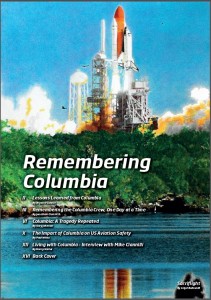

“It’s really important to understand the true nature” of how the Columbia accident came to be, Ciannilli points out. “I saw a lot of great things after the accident being put into effect,” he said, but notes: “you just can’t forecast beyond where we stopped flying.” And that’s perhaps where the challenge lies in a post-Columbia world. Will NASA and other space organizations, agencies, and companies retain these lessons? Or are we doomed to repeat our tragedies every couple decades, when no one thinks to remember the last one? To read more from this interview including Ciannilli’s experiences from the debris search, check out the special report Remembering Columbia in the Winter Issue of Space Safety Magazine, available online January 25th.

“It’s really important to understand the true nature” of how the Columbia accident came to be, Ciannilli points out. “I saw a lot of great things after the accident being put into effect,” he said, but notes: “you just can’t forecast beyond where we stopped flying.” And that’s perhaps where the challenge lies in a post-Columbia world. Will NASA and other space organizations, agencies, and companies retain these lessons? Or are we doomed to repeat our tragedies every couple decades, when no one thinks to remember the last one? To read more from this interview including Ciannilli’s experiences from the debris search, check out the special report Remembering Columbia in the Winter Issue of Space Safety Magazine, available online January 25th.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](https://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply