While asteroids and radiation are truly some of the biggest challenges we face in human expansion into space, there is one often overlooked aspect that could be of even greater importance – the Human Element. A community of thousands would live among the largest of these colonies, and their day-to-day lives would have to be one of the most important considerations in such an endeavor. Even the smaller colonies, the asteroid mining camps and construction housing, would require a large number of people to live together in an incredibly harsh environment for a long period of time. Space may sound like an exciting place, and while the splendor it provides is beyond compare, there is also crushing isolation, being cut off from friends and family, and the constant reminder of danger lurking just outside the protection of your small home. Space can be scary.

While picturesque, the stresses of living aboard the ISS can be immense, and give us a profound look at the difficulties that lay ahead (Credits: NASA).

Psychology in Space

Unlike the subjects of radiation and asteroids, we have a great deal of firsthand information and study on the effects of long-term living aboard a space station. The crews aboard the ISS have spent countless months in a relatively tiny habitat under the constant monitoring of behavior scientists and psychologists at NASA and other space agencies. This has provided ample opportunity to examine the effects of long-term space habitation. We can also look to a wealth of knowledge involving similar situations, such as submarine crews[1], rig workers, and other positions that require an extended amount of time in relative isolation.

There have been several formal studies on astronauts’ mental wellbeing, with most of the studies seeming to show very few major mental issues developing even over extended stays aboard the ISS[2]. This is not to say a number of psychiatric problems have not been recorded aboard the ISS; the most common are generally a variety of forms of anxiety and depression, resulting from the adjustment to the challenges of living and working in space. Many astronauts have complained of home sickness and loneliness. While these issues can be managed with a variety of psychotherapies and psychoactive medicines, there is no easy answer to these problems, only that any crew of the earliest basic, small habitats should be pre-screened for mental illnesses and susceptibility similar to how astronauts are currently screened.

One study assessing the mood and group dynamics of teams aboard the ISS showed a series of issues arising early in the mission. Some crew members became more reserved and engaged in behavior dubbed ‘psychological closing’ whereby they would decrease the scope of their communication with ground control and their crewmates, in some cases viewing them as ‘opponents’ – this in some cases caused issues with group cohesion. While this is dangerous on ISS, it would be even more so with a private crew working a near Earth Object (NEO) in relative isolation. Mandated social time and joint activities abated many of these effects, and the inclusion of highly social people in support roles also helped diminish these issues.[3]

Submarines sometimes stay underwater for weeks without resurfacing, and the day to day life of the crew aboard closely resembles what life for an early space worker would be like (Credits: US Department of Defense).

Pioneer Life

As with radiation, the people at greatest risk from these issues are the earliest pioneers. It would seem that the major issues arise from the sense of isolation and the small, enclosed quarters that astronauts experience aboard the ISS. Further, the general stresses of working in space combined with the various disruptions and adaptations the men and women aboard the ISS must deal with contribute massively to their psychological health.

The small crews manning these outposts would likely live a similar life to the men and women aboard the ISS. Working a significant percentage of their time, living in a small building and without many of the benefits or comforts of even the most remote of jobs on Earth – these people would presumably be well compensated for their work establishing a foothold among the stars. Some believe that robotic workers could take the place of these early pioneers, and while that would certainly simplify this stage in human expansion into space, development into the kind of advanced robotics that would make this a possibility has been slow. Pioneers would need to be versatile and respond creatively to unexpected scenarios – the very characteristics at which robotic explorers have always been challenged.

Coming of Age

As space industry and colonization grows, the sense of isolation would diminish. As more and more people spend significant time in space, recreational options and larger quarters could also be established. Cottage industries will arise, selling supplies and services to the workers of asteroid mining missions or construction operations, further diminishing the effects of isolation and the sensation of being trapped, alone in space.

The isolation and stresses of working aboard an offshore rig may be similar to those experienced by future space workers (Credits: Agência Brasil).

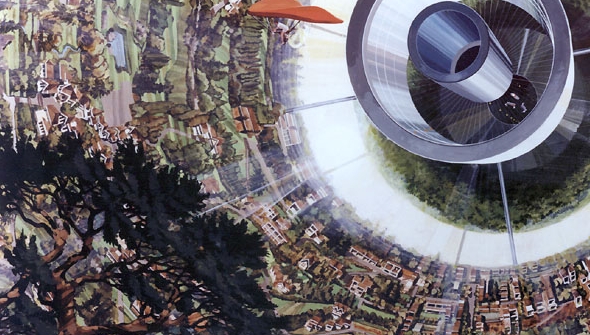

Eventually, as larger scale colonies are established and become self-sufficient, it follows that such a community would not suffer the negative psychological effects that our current astronauts do. As soon as a population of even modest size begins spending a significant time living in space, service industries will inevitably develop in any mid-level colonies. Colonies the size of Gerard O’Neill’s Island Three would functionally be a city in space, with cinemas, restaurants – any amenity the citizens of space could want in life.

Larger scale habitats (those containing 100 people or more) would not likely have many of the same issues as our current small scale stations experience. The sheer size of such a habitat would grant the workers more space, the nature of their work would grant them more downtime, and the general design of the habitat could more easily simulate an Earth-like environment with pseudo-gravity provided by rotation and the possibilities for gardens, kitchens, and other amenities that would alleviate some of the need to adapt to a radically different environment. Work crews aboard these habitats would still have to contend with the lack of Earth communication, as well as any issues arising from interpersonal friction, but these are problems we find mirrored in Earth jobs: the aforementioned oil rigs and Alaskan workers continue to function with relatively few major problems. The need for onboard psychologists, pre-screening, and mandated contract limits should be considered to minimize the potential issues that could arise.

The day to day life of a worker aboard a mid-sized habitat would probably be something between an oil rig worker and a submarine pilot. Not glamorous by any stretch of the imagination, uncomfortable and full of difficulties, but not an altogether unimaginably difficult posting. The view, at least, would be enviable.

Artist’s rendition of the inside of a Bernal sphere, showing human-powered flight near the low-g center of the habitat (Credits: Rick Guidice/NASA).

Shopping Malls in Space

The largest of these proposed colonies, like those envisioned by O’Neill, would have none of these potential drawbacks. These massive cities in the sky would house thousands of people and include any service or business found in any major town or city on Earth. Theaters, restaurants, hospitals, schools, libraries, public transportation, and shopping malls – the National Space Society even suggests that large settlements must include a large amount of park space, with flowing rivers and fish[4], as well as other forms of life such as birds and small mammals. All of this powered with clean, infinite solar energy gathered by massive solar arrays constructed in-situ. Life aboard Island Three would even have some amenities and entertainment we lack on Earth. Zero Gravity sport could be conducted in the center of the habitat, where the gravity provided by the rotation of the habitat wouldn’t exist[5]. A whole host of activities would likely arise, using zero gravity and the surrounding space as inspiration. O’Neill often mused in his writings on zero gravity ballet and ‘space hotrods’; the idea of humanity finding joy in their new home is a comforting, familiar one.

The daily life of these inhabitants would be almost indistinguishable from our own-besides the aforementioned zero-gravity activities, and the strange view. Many would work constructing and designing new habitats or space-projects, but a huge number of people would work maintaining the habitat and managing businesses. Space living comes with a whole host of benefits and comforts that we on Earth cannot enjoy, such as lower gravity homes for the elderly and disabled. It’s hard to imagine anyone finding a colony on this scale difficult to live in.

The comfort and day to day life of our astronauts is not an overwhelming priority (although it is a growing one), but for a civilization to grow and expand in space, this must be a primary concern from early on. The men and women who first begin living and working among the stars will carry with them the legacy of our species, and their mental and social stability is of upmost importance. They will be laying the foundations for the most challenging and rewarding expedition humanity has ever set upon.

References

[1] http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/92/387/343 – A medical study of 71 submariners showing a very small rate of mental illness, hypothesized as due to the success of the screening process.

[2] http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/607107main_PsychologySpaceExploration-ebook.pdf – This book discusses one of the major studies of on-board psychiatric issues, stating mostly minor levels of depression and anxiety, with no reported major mood disorders recorded during the entire history of space missions.

[3] The Russian scientist Vadim Gushin has published extensively on the subject, using many of these studies as a basis for a large body of work – http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vadim_Gushin/publications

[4] http://www.nss.org/settlement/nasa/75SummerStudy/Chapt8.html – This section contains recommended subjects for research that could lead to space colonization, among the more scientific subjects of radiation shielding lies “Detailed metabolic requirements for plants and animals” and “sustained condensed humidity for humans, for fish and for crop irrigation” as well as several other subjects of note.

[5] http://www.spacefuture.com/archive/zero_gravity_sports_centers.shtml – an extensive look at the subject of zero gravity sports.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](https://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Solution:

– Provide the isolated people with virtual reality (VR) equipment like the Oculus Rift, plus virtual worlds that will be breathtakingly spacious and beautiful.

– Beaches and oceans, vast, grassy sunny savannas with wildlife and rivers, huge mountain ranges, gliders high in the sky, stadiums full of cheering people watching a marvellous game.

– Make them ‘shared’ experiences with their crewmates and avatar robots of their family, friends, and favourite others.

– Add ‘presence’ enhancer experiences like airflow over the face, heat or cold, vibration, bumping, tipping and turning. The brain is easy to fool apparently, from experiments done in VR.

– I think a key factor is the amount of oxitocin in the blood (the natural chemical secreted in our bodies that makes us happy when we’re with people). I think VR technology could cause great comradeship from crewmates and even attractive, artificial intelligence robots that provided very affectionate types of interactive learning.

– By the way, someone should equip Julian Assange with such equipment to increase his enjoyment of life.

Bruce Thomson in New Zealand.