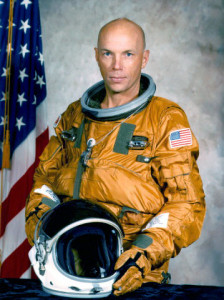

Space Safety Magazine introduces a new series of articles dedicated to space medicine and astronauts. In the series, we will present and explore topics involving medical emergency management in space, astronaut training, and issues coming from long-duration missions in space. As the first chapter, we present a profile interview with the physician and retired NASA astronaut Story Musgrave.

Musgrave’s biography is full of anecdotes and inspirational events. Before becoming an astronaut, he worked as an electrician, a mathematician, a computer programmer, a mechanic, a pilot, and a surgeon. His 30 year career at NASA spanned from the Apollo era to the Space Shuttle program, during which he flew six Space Shuttle missions, beginning in 1983 aboard Space Shuttle Challenger and ending his astronaut career in 1996 aboard Space Shuttle Columbia, at the age of 61. Musgrave, one of NASA’s most experienced astronauts, is also the only one to have flown on all five Space Shuttles.

Despite his outstanding experience and achievements, Musgrave does not think that going into space somehow changed his vision of life; in other words, he did not experience the “overview effect” as described by many of his space colleagues. The overview effect is a cognitive shift in awareness which was reported by some astronauts and cosmonauts during their spaceflights. Musgrave claims he always had that kind of sensibility, and he does not believe that the overview effect has really had a significant effect on humans either as individuals or as a species.

“I have flown with 27 different rookies, I’m not sure that there is anyone around that has flown with so many people. I am a people-watcher too. I have seen how they react, how they changed, I observed them in the years to come and I do not believe that the overview effect had a significant effect on them.”

Musgrave, who also observed the effect through the years, objects that humanity also did not change after having seen the “Blue Marble” image taken by Apollo 17 or the “Pale blue dot” from Voyager 1. According to Musgrave, if the overview effect had truly imparted a permanent cognitive shift, humans would have started cooperating in peace and looking after the Earth but “that has simply not happened.”

Musgrave is anchored on the end of the Remote Manipulator System arm during STS-61, Hubble’s first servicing mission (Credits: NASA).

Saving Hubble

During his time at NASA, Musgrave worked on space suit technology and development, space shuttle software, and he assisted with servicing design elements of the Hubble Space Telescope, which then contributed to the repairs he conducted. The mission, first of five servicing missions dedicated to the space observatory and probably one of the most complex in the Shuttle’s history, was launched on December 2, 1993 aboard Space Shuttle Endeavour. In their 11 days in orbit, the astronauts had to restore the Hubble’s vision capability by installing a new main camera, instrument upgrades, and new solar arrays. Musgrave took part in three of the five EVAs scheduled, each lasting between 7 and 8 hours. The mission required perfect coordination and a deep understanding of the spaceborne observatory’s components and of the actions needed to recover its sight.

“I designed it for 18 years before I went to fix it. They told me in 1975 to find every possible problem that I could have imagined and that they could get into. I identified every possible failure and I came up with tools and procedures to fix [it] with a spacewalk. They did not tell me to fix it robotically, but to fix it with a spacewalk.”

Hubble was launched in 1990 and it had a significant failure immediately, with 13 major systems broken. Because of his vast experience in the Hubble’s systems, Musgrave was NASA’s natural choice to take part in the servicing mission.

“We were not simply trained for the mission, we were designing the mission”

Theatrical poster for the film Mission to Mars (2000). Musgrave may not want go to Mars but he made a cameo appearance as 3rd CAPCOM in Brian De Palma’s movie on which he also served as a consultant (Credits: Touchstone Pictures, Spyglass Entertainment).

Mars and Medicine

Musgrave, 79 in August, does not share the dream of Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space in 1963, who declared that she would go to Mars, even if the mission would be a one-way trip.

“I personally would go, but it’s not appropriate. If you are going to spend all those resources, you want someone to live there for 20 or 30 years.”

Musgrave has a severe opinion of NASA’s current plan for Mars, which he describes as lacking of a decent vision.

“If NASA would put in place the kind of project management we had in the’ 60s, when we did Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo within 8 years and in the same timeframe we did our first space station, then it is a very nice way to get outside the Earth orbit – Mars or other destinations.”

Astronaut Scott E. Parazynski retrieves supplies from Space Shuttle medical kit on the Space Shuttle Discovery during STS-95 (Credits: NASA).

However, during such long missions outside the “cradle of humanity,” it is certainly not unlikely to have medical emergencies on board. The recent case of a norovirus outbreak on a cruise ship sailing in the Caribbean Sea clearly shows some of the risks that have to be taken into account during long journeys in confined environments. During the Space Shuttle program but also now, with the International Space Station, in case of more serious medical emergencies, the astronauts are just a few hours away from professional medical care.

“If you have a medical emergency in the afternoon on the Space Station or on the Space Shuttle, the next morning you find yourself in a very advanced medical center. On Mars, you are not going to be home for over a year or two. The basic question is how much medical equipment you will need to have on board.”

Musgrave helped design the medical equipment used on the Space Shuttle in order to deal with particular emergency conditions or to tide over an injured crew member for a few hours while the shuttle deorbits. The Space Shuttle medical set consisted of a pharmacological kit with bandages, drugs and medications, and other emergency tools, such as a surgical kit, tracheotomy instruments, etc. It did not contain a defibrillator, which is nowadays deployed on the ISS. In the case of a mission to Mars, however, Musgrave sees a necessity for the presence of trained medical personnel as well as more specialized and different medical equipment to face the many situations that the future Martian explorers could get into.

Image caption: Story Musgrave with the crew of STS-80, in 1996 (Credits: NASA).

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](https://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Thanks for the well written article.

Bob Clark