The smaller ellipse is the newly revised landing target for Curiosity (Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/MSSS).

NASA’s massive nuclear powered Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity launched on November 26, 2011 and will not land until August 5, 2012. But even as it journeys through space, the rover’s parameters are ungoing some tweaking.

On June 11, NASA announced a change to the rover’s landing conditions. Curiosity will employ a unique landing system, descending from a Sky Crane by a cable that is able to handle its high mass better than a traditional airbag softened landing. Engineers have been studying the landing scenario since November and have come to the conclusion that is it capable of greater precision than initially thought. The rover will still land in Gale Crater, but within a 7×20 km region instead of a 20×25 km region.

“We’re trimming the distance we’ll have to drive after landing by almost half,” said Pete Theisinger, Mars Science Laboratory project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “That could get us to the mountain months earlier.” The mountain is Mount Sharp, a destination for investigation by Curiosity but also a landing hazard as the feature resembles its name only too well.

The change is enabled by software upgrades that were uploaded to the craft in June. Further upgrades to software for surface operations will be uploaded in the week after the August 5 landing, according to NASA.

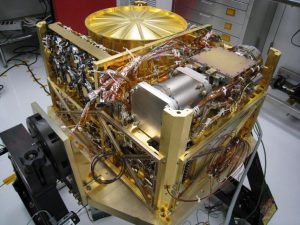

The Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument will analyze samples of material collected by the rover's arm. It is not expected to have trouble with teflon particles, but results may be skewed with respect to native carbon compounds (Credits: NASA).

All of the post-launch reviews of Curiosity have not produced such rosy results, however. NASA also revealed that scientists have been studying how to deal with expected teflon contamination from the rover’s drill head. The drill already came under scrutiny prior to launch for deviating from planetary protection protocols. Now it seems that the drill could also complicate science objectives.

Teflon, the well known non-stick material, was used to coat the drill, but tests at JPL have shown that the coating can come off during use, mixing with powdered geological samples. “The material from the drill could complicate, but will not prevent analysis of carbon content in rocks by one of the rover’s 10 instruments. There are workarounds,” said John Grotzinger, the mission’s project scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Those workarounds seem to consist of not using the drill’s more aggressive hammering action in favor of the gentler rotary motion. If even that fails, it has been proposed that the drill be abandoned altogether, instead using the rover itself to break up rocks into manageable pieces by driving over them.

Further complications are bound to crop up once Curiosity actually reaches the Martian surface. Until then, its scientists and engineers can only worry, test, tweak, and hope.

Watch an animation of Curiosity’s intended landing and surface operations below:

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply