Motor casing of a Payload Assist Module Delta stage which re-entered the atmosphere in January 2001 and landed in Saudi Arabia (Credits: NASA).

Source: Michael Listner for The Space Review: NASA has announced that Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), launched by the shuttle Discovery in September 1991, is expected to reenter the atmosphere within the next week. The satellite, 35 feet (10.7 meters) long and 15 feet (4.5 meter) wide, is unlikely to reenter over a populated area; however, 26 large pieces are expected to survive reentry.1

Debris from satellites and their boosters surviving reentry and falling on land is not uncommon. On March 2 of this year there was a report of the titanium motor casing of the STAR-48B third-stage of a Delta II rocket being recovered in Uruguay after spending seven years in orbit.2 On March 19, the second stage from a Zenit-3 SLBF, which launched a Russian weather satellite into geosynchronous orbit, reentered the atmosphere over Utah and the extreme northwestern part of Colorado. Three days later, a metal sphere with Cyrillic markings that appears to have been part of the pressurization system for the Zenit stage was found in a remote area of Moffat County in Colorado.3 In both cases, the debris in question apparently caused little or no damage as apparently neither the United States nor the Russian Federation have been held to account.

While debris from UARS is unlikely to fall on land, let alone populated areas, NASA has not ruled out that possibility. Nick Johnson, the chief scientist of NASA’s Orbital Debris program, noted that the odds of UARS reentering over a populated area are very low, but in the same vein NASA officials have cautioned the public that any pieces of UARS discovered remain the property of the United States government. While this statement appears to be couched in terms of memorabilia hunters and private collectors, the statement also sets the stage for the United States’ legal responsibility for any damage that may be caused by the debris from UARS that survives reentry. While such an occurrence is not ideal, it could present an opportunity for the United States to bolster the existing body of international space law.

Existing international space law and its problems

The current body of international space law is embodied in five international treaties: the Outer Space Treaty, the Rescue Agreement, the Liability Convention, the Registration Convention, and the Moon Treaty. These accords, starting with the Outer Space Treaty, were couched in terms that allows for a broad interpretation of the obligations of the signatories.

A case in point is the Outer Space Treaty. With the exception of Article IV, which strictly prohibits the placement of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction in outer space, the Outer Space Treaty is more a less the formalization of principles intended to be legal obligations upon the signatories. These legal obligations are couched such that they are open to broad interpretation, which invariably leads to signatories interpreting the provisions of the Treaty in a manner that allows them to circumvent or otherwise avoid them. The net effect is that the legal significance of the provisions is weakened, which affects the strength of international space law in general.

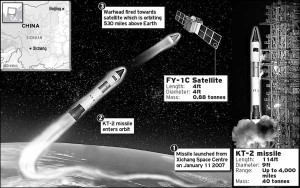

A recent example of this is the contention that the People’s Republic of China violated its legal obligations under Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty when it failed to consult with the international community before its test of a direct-ascent anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon against the weather satellite FY-1C. The resultant debris from the test and the hazard it created in the space environment was the scenario that Article IX was intended to address and avoid. Several days after the test, China’s government insisted that the test was in compliance with international law. This statement suggests that either China interpreted Article IX as not applying to their ASAT or that they simply chose to ignore it. Either way, the net effect was that the space environment was contaminated without forewarning to the international community, and the authority of Article IX was diminished as was the body of international space law in general.4

A recent example of this is the contention that the People’s Republic of China violated its legal obligations under Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty when it failed to consult with the international community before its test of a direct-ascent anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon against the weather satellite FY-1C. The resultant debris from the test and the hazard it created in the space environment was the scenario that Article IX was intended to address and avoid. Several days after the test, China’s government insisted that the test was in compliance with international law. This statement suggests that either China interpreted Article IX as not applying to their ASAT or that they simply chose to ignore it. Either way, the net effect was that the space environment was contaminated without forewarning to the international community, and the authority of Article IX was diminished as was the body of international space law in general.4

Ironically, the United States had an opportunity to strengthen the authority of Outer Space Treaty, in particular Article IX, when it announced its plan to intercept its crippled satellite USA 193. As part of its preparation to inform the general public and international community of the impending intercept, the United States, through NASA, briefed the UN’s Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) concerning its plans for USA 193. However, instead of citing Article IX as its rationale for informing the international community, it took the position that the planned intercept of USA 193 did not trigger its obligations under Article IX. Arguably, the United States may have been correct in its legal assessment that the intercept did not trigger its Article IX obligations, but at the same time it missed an opportunity to set a precedent in international space law. Invoking Article IX would have set a precedent for future activities similar to the USA 193 intercept by other signatories to the Treaty, and it would have also bolstered the legitimacy Article IX as well as the general body of international outer space law.5

The above illustrations highlight only one of the problems faced by international space law. The remaining four treaties each designed to enhance the Outer Space Treaty also face similar problems in terms of interpretation and enforceability, with perhaps the Moon Treaty facing the greatest hurdles considering that neither the United States, the Russian Federation, nor China have recognized it as legally binding upon them. Given these inherent problems, how can a defunct research satellite that is falling to earth create an opportunity for the United States to reaffirm and strengthen international space law? The answer lies in the Liability Convention.

The Liability Convention and missed opportunities

The Liability Convention of 1972 expands upon the principles of liability for damage caused by space objects introduced in Article VII of the Outer Space Treaty. The Liability Convention envisions two scenarios where damage could be caused by a space object. The first scenario envisions a space object that causes damage to the surface of the earth or an aircraft in flight. The second scenario envisions an event where a space object causes damage someplace other than the surface of the earth, i.e. outer space or another celestial body.

For each scenario there is a separate standard of liability. In the first scenario a state is considered strictly liable for any damage caused by a space object launched even in the face of circumstances that are outside a state’s control. If more than one state is responsible for the launch of the space object in question those states then will be held jointly and severally liable for any damage caused. The second scenario under the Liability Convention holds a more burdensome standard of liability in that it employs fault liability. Under this standard, a state will be considered liable only if it can be shown that it was due to the fault of the state or states responsible for the launch of the space object, as the case may be.

The first and perhaps most infamous application of the first scenario envisioned under the Liability Convention was the reentry and subsequent crash of the RORSAT Cosmos 954 on January 24, 1978, in the Northwest Territories of Canada. The crash spread radioactive debris from the onboard nuclear reactor that powered Cosmos 954’s radar. The debris from the satellite, which was registered to the then Soviet Union, was located by Canadian authorities and initially identified as coming from Cosmos 954. Canada’s Department of External Affairs issued a diplomatic communiqué invoking Article V of the Rescue Agreement, whereby the Canadian government informed the Soviet Union that per its obligation under that Agreement it discovered what it believed to be the remnants of Cosmos 954. After the identity and origin of Cosmos 954 was confirmed, the Canadian government made its formal demand to the Soviet Union pursuant to the Liability Convention for costs associated with the cleanup of the debris and any resulting damage.

The diplomatic efforts of both governments led to an agreement for compensation, but despite the use of international space law as a means to resolve the incident, Cold War politics was likely the motivating factor. The resulting agreement and compensation actually paid by the Soviet Union is seen more as a punitive measure for the Soviet Union violating Canadian airspace than a means of compensation for the costs of cleanup and damages under the Liability Convention. The end result is that instead of enhancing the body of international space law, both Canada and the Soviet Union efforts may have done more harm to it than good.

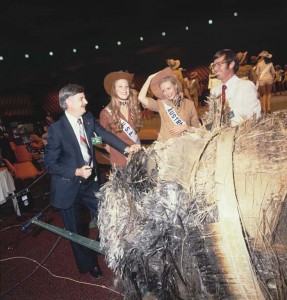

A piece of Skylab debris on display at the 1979 Miss Universe contest held in Perth (Source: the Australian Government).

Another incident that could have implicated the Liability Convention and international space law occurred over a year later when Skylab fell from orbit on July 12, 1979. The United States assured the international community at the time that any debris from Skylab that survived reentry would likely fall in the Indian Ocean. Contrary to that assurance, several pieces of debris fell in the Australian town of Esperance, and authorities in Canberra were alerted.

Shortly thereafter, officials from NASA arrived to inspect and collect samples of the debris. The citizens of Esperance were encouraged to bring pieces of debris to the officials for which they were given a commemorative plaque and a model of Skylab. The officials from NASA did not collect all the debris, and in one case a piece of debris was turned over to the San Francisco Examiner, which was offering a $10,000 reward to the first person who could bring a piece of Skylab to the paper’s newsroom. Aside from the plaques and models, there was no official compensation for the debris falling on the town; however, a ticket was issued a year later by the president of the town council against the United States for littering, which the United States government has yet to pay.6

Otherwise, no formal claim was made by Canberra under the Liability Convention for the incident, and one can only speculate as to Canberra’s rationale for not doing so. It is noteworthy that it seems the United States never officially identified the debris as coming from Skylab, and the fact that the United States never collected all the debris seems to bear that out. Still, it is possible that the lack of appreciable damage or politics alone figured into Canberra’s decision not to press a formal claim for compensation against a Cold War ally. That a formal claim wasn’t filed represents another missed opportunity that could have otherwise set a legal precedent bolstering the legitimacy of international space law.

The Liability Convention and its implications for UARS

The potential for debris from UARS landing in a populated area creates the possibility that the Liability Convention may once again come into play. As noted earlier, an agent of the United States government publically stated that any debris from UARS remains the property of the United States government, thus if a claim for damages is made, it may be more difficult for the United States to shrug its shoulders and walk away as it appears to have done with Skylab.7

Per the Rescue Agreement, a claimant that found debris would be required to inform the United States of its discovery and facilitate the return of the debris to the United States. The claimant then would be in a position to file a claim for damages from the debris from UARS under the first scenario under the Liability Convention holding the United States strictly liable for those damages. At this juncture the United States would be left with two choices: Either present a legal rationale to ignore a legitimate request for compensation or admit liability and enter into good faith negotiations to address that request.

While the former may be difficult to achieve given the strict liability standard of the Liability Convention under the first scenario, it is not entirely insurmountable. Considerations of political rhetoric aside, denying liability would only serve to further weaken the authority of international space law. Furthermore, taking this path would certainly weaken the long-standing position by the United States that the existing in-force regime of international space law is sufficient to guarantee the right of all nations for access to, and operations in, space.8

While the legal arm of the United States might be loath to even consider the latter choice, the decision to do so would not be without its benefits. There is the inherent risk that the claimant would take advantage of an admission of liability and make a claim for damages far and above what actually occurred. There is also the risk that an admission of liability would be used by a claimant to get its fifteen minutes of fame on the world stage by parading the debris in front of the media and making a spectacle for all the world to see. However, the potential benefits of admitting liability would far outweigh the temporary inconvenience these risks would present.

The primary benefit to the United States in choosing to accept liability is that doing so would set a precedent that would strengthen the authority of the current body of international space law. Not only is this good for the legal regime in general, but it would also bolster the position by the United States that the current body of international space law is sufficient to guarantee the right of all nations of access to, and to operate in, space.

The United States could also find itself in a better position to go on the diplomatic offensive against those nations who prefer an expansion of the current legal regime, such as the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China. By accepting liability under international law, the United States could demonstrate that one of the solutions to the issues surrounding access to outer space is not to create more treaties, but rather for nations to abide by the current ones. The United States could find such leverage useful as it prepares to convince the international community that transparency and confidence-building measures (TCBMs) can be used to build upon the current body of international space law instead of creating new treaties to address old problems.9

Certainly not least of the possible benefits the United States could receive from fulfilling its obligations under the Liability Convention is the integrity that would allow it to stand up on the world stage and demonstrate that it not only supports support international space law through its word but through its actions as well. Standing such as this could silence or, at the very least, give pause to the political rhetoric of those who speak of their support to the precepts of international space law while at the same looking for opportunities to avoid it.

Conclusion

The Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) during deployment from Space Shuttle Discovery in September 1991 (Credits: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center).

The most likely—and preferred—outcome of the UARS reentry is that the debris that survives reentry falls harmlessly into the ocean without damage to person or property. However, if some of that debris should find its way to populated areas, the world will look to see how the United States responds. If it chooses to take the high road and accept liability, any legal detriment it incurs will be offset by the positive effects upon its stature in the international community. Most importantly, the authority and soundness of international space law would be preserved and strengthened in the present and the future.

Originally published in The Space Review on September 19, 2011. Reproduced with permission of the author and the editor.

Footnotes

1Tariq Malik, “Dead NASA Satellite Falling from Space But When & Where”, SPACE.com, September 9, 2011.

2“Reentry of U.S. Rocket Stage over South America”, Space Debris Quarterly, Volume 15, Issue 3, July 2011.

3“Russian Launch Vehicle Stage Reenters over U.S.”, Space Debris Quarterly, Volume 15, Issue 2, April 2011.

4There is the argument that the international community, in particular was aware the PRC was preparing for such a test; however, the question remains whether that knowledge relieved the PRC of its obligations under Article IX.

5For an excellent analysis of Article IX and its applicability to the FY-1C and USA-193 intercepts, see Michael Mineriro, FY-1C and USA-193 ASAT Intercepts: An Assessment of Legal Obligations Under Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty, Journal of Space Law, Volume 34, p.321.

6Stewart Taggert, “The Day Skylab Fell”, Wired, March 22, 2001.

7It is presumed in this hypothetical that the claimant where the debris falls is in fact a signatory of the international space law treaties.

8Excerpt from the Statement as delivered by Karen E. House, United States Public Delegate to the 63rd Session of the UN General Assembly, Delivered in the Debate on Outer Space (Disarmament Aspects) of the General Assemblies First Committee, October 20, 2008.

9See Michael Listner, “TCBMs: A new definition and new role for outer space activities”, DefensePolicy.Org, July 7, 2011

Michael Listner is an attorney and policy analyst with a focus on issues relating to space law and security. He is a Senior Contributor at DefensePolicy.Org and can be contacted atmichlis@alumni.regent.edu or via Twitter @ponder68.

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply