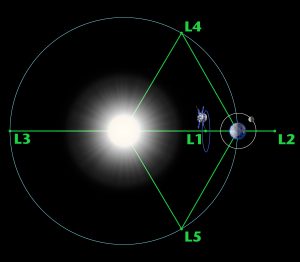

NASA’s Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) orbits a point between Earth and the sun called a the first Lagrange point, or L1. Sitting well outside of Earth’s magnetosphere, ACE can observe material streaming off the sun before it enters near-Earth space (Credits: NASA/H. Zell).

Source: NASA

The Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) is Earth’s vanguard. Orbiting around a point 900,000 miles away between the Earth and our sun, this satellite is ever vigilant, recording the combination of radiation — from the sun, from the solar system, from the galaxy – that streams by. None of this radiation can harm humans on Earth, but the biggest bursts of particles from the sun can flow into near-Earth space causing a dynamic space weather system that can damage satellites and interfere with radio communication transmissions and navigation systems.

When one of these bursts of solar material – known as a coronal mass ejection or CME – erupts from the sun toward Earth and passes ACE, the instruments onboard the spacecraft observe the increase in particles and automatically transmit this information to publicly available websites within five minutes. This offers a crucial advance warning of some 20 to 60 minutes to those who need to protect their technology from the effects of space weather, such as satellite operators, airplane pilots and utility companies.

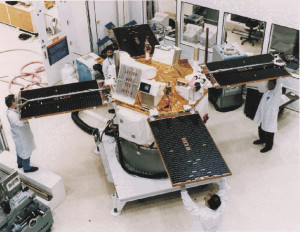

ACE is, therefore, a crucial component of NASA’s fleet, but its job as sentinel is, in fact, just a small piece of what ACE has accomplished since it launched on August 25, 1997. In its first 15 years, the spacecraft has helped determine the composition of the vast sea of flowing particles surrounding Earth. ACE also serves as a sentinel that helps measure the input — the solar wind — that drives the dynamics of the magnetosphere.

“We knew ACE would help with space weather monitoring, but fundamentally, it’s a science mission,” says Eric Christian, the deputy project scientist for ACE at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “It’s called a ‘composition’ explorer, because one of its main goals was to identify and study all the components of space radiation.”

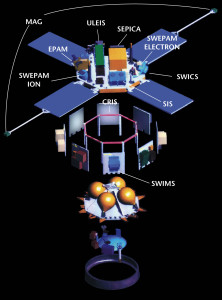

To tease out the various components of these space particles, ACE’s nine instruments were designed to observe the wide range of particles in space, differentiating between various elements, energies and charges. ACE had two jobs: figure out where different kinds of particles originated and how they got an extra kick of speed, since a large number of the individual particles in space are traveling faster than scientists would expect based solely on the temperature of the material, suggesting that additional acceleration processes must be at work.

Based on ACE data over its first 15 years, we now have a much better understanding of the zoo of space particles and what causes their motion. The slowest particles with the lowest energy come from the solar wind, traveling at speeds of about 200 to 500 miles per second. Much quieter and less explosive than CME’s, the solar wind nonetheless displays a complex and dynamic flow. For example, as high speed solar winds course off the sun, they can over take slower winds, and create shock waves to form giant, spinning eddies known as co-rotating interaction regions (CIRs) and these CIRs are an important component in accelerating particles.

Higher energy particles, known as solar energetic particles or SEPs, come from the sun, driven by fast CMEs and solar flares. These solar eruptions create what’s called interplanetary shocks – much like a bow shock from a plane – that force the particles ever faster through space. These shocks can travel long distances, continuing to occur even as they pass by ACE, allowing scientists to study the acceleration processes in situ.

Particles also fly past ACE from the outer edges of the solar system and even from interstellar space. “Pickup” ions are believed to be created when neutral atoms from the galaxy collide with solar ultraviolet light or the solar wind to make charged particles. ACE cannot see the neutral atoms, per se, but can observe the pickup ions they create. Finally, at very high energies are the galactic cosmic rays, thought to be accelerated by shock waves from supernova explosions in our galaxy.

All of this information about different types of particles and what causes their acceleration contributes to our understanding of the giant space weather system of material and magnetic energy that surround the sun, Earth and the planets. By improving our understanding of that system, scientists can make even better use of the constant updates ACE provides about what solar energy is headed our way.

ACE science has also gone beyond the heliosphere. By observing galactic cosmic rays, the spacecraft has also advanced astrophysics understanding of how elements are created in supernovae. It is known that the intense heat from a supernovae – the giant explosion at the end of a star’s life – fuses smaller elements into larger ones. The makeup of cosmic rays suggest that most of them come from the concentrations of massive stars in certain areas, galactic superbubbles, which are regions where many supernovae explode within a few million years. Recent observations of a cocoon of freshly accelerated cosmic rays in the Cygnus superbubble by the Fermi gamma-ray observatory support this theory.

Although there has been some degradation in ACE’s instruments, fuel and power are sufficient to keep it functioning for another decade. Not only will this help keep ACE in place to take space-weather measurements, but it also lays the groundwork for continued science on how the sun’s energy and the solar wind affect our near-Earth space.

As missions such as NASA’s Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP), due to launch at the end of August 2012, the Magnetospheric Multiscale mission (MMS) due to launch in 2014, and the Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS), launched in 2007, seek to understand how Earth’s magnetosphere responds to incoming energy, it is ACE, lying outside the magnetosphere and facing the sun, which can describe what input from the sun caused those changes.

For more information about ACE, visit: http://www.srl.caltech.edu/ACE/

For the latest Space Weather Now (including ACE measurements) from NOAA, visit: http://www.swpc.noaa.gov/SWN/index.html

Correction: The ACE satellite is 15 years old, not 50 as originally reported. Space Safety Magazine thanks alert reader Neil for catching this error. ~The Editor

![A trajectory analysis that used a computational fluid dynamics approach to determine the likely position and velocity histories of the foam (Credits: NASA Ref [1] p61).](https://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/fluid-dynamics-trajectory-analysis-50x50.jpg)

Leave a Reply